|

Meredith Denning An old geographer that I know once asked me, “Isn’t environmental history just historical geography?” and then we had a long talk about methodology, the agency of non-human actors, and interdisciplinary research in general. I think I convinced him that EH is a field in its own right, though it may simply have been a case of my dad letting me win an argument. In any case, I’m absolutely convinced that maps are a very important part of any presentation of historical research, and I’ve made a few attempts to pick up GIS skills at Georgetown. I made my first attempt while working as assistant to the Director of Doctoral Studies, charged with creating useful workshops for history grad students. I asked two of the campus librarians, trained in ArcGIS at university expense, to run a series of workshops to teach interested students to use the software. The three of us put together an introductory day and I sent out invitations. A dozen people showed up for the first session, but it quickly became clear that (a) the instructor detested GIS and (b) the questions that historians wanted to address using maps were very, very different from the questions that the software developers envisioned. Even allowing for the time and effort needed to acquire the specialized vocabulary of the ArcGIS program, it didn’t seem well-adapted to historical research. Since then, two historians have created and run GIS workshops at Georgetown and while the experiences they shared did reinforce the message that ArcGIS takes a lot of time to learn, I’ve begun to appreciate the ways in which it can be used. It really helped to learn from historians, because they understood what I and other grad students were trying to accomplish. For example, non-GIS historians often want to: - create digital files that combine maps or charts from archival documents with modern maps. - put customized points and lines on an accurate map In fall 2016, Michal Polczynsky, a Georgetown alumnus who studies the medieval history of the Black Sea region, invited history grad students to bring a digital copy of an archival document to his GIS workshop. I brought along a scanned page which showed a detailed map of the Canada-US border between Lake Huron and Lake Erie. While we took copious notes, Mich explained how to turn our scanned documents into a semi-transparent ’layer’ that could be superimposed over a modern satellite map, almost like laying two overhead transparencies on top of each other. We linked the current and archival maps by identifying points that were common to both. For example, the city of Detroit was on my archival map and on the modern satellite map. Since the archival documents were rarely perfectly accurate, they tended to look rather stretched and odd once we had done the work of linking these matched points (see photo). However, it was fascinating to see where the historical mapmakers had been mistaken, and in Mich’s work, the combination of satellite imagery and medieval maps had enabled him to locate long-destroyed fortifications and buildings with precision. Geoff Wallace, who studies the environmental history of the Yucatan and was visiting us from McGill, conducted a workshop this spring that was very helpful for putting points and lines on a graph. He explained the differences between raster and vector data quickly but clearly. (Raster data is plotted on a grid of squares that cover the area in which a given physical feature lies, while vector data are lines, points and shapes). Having done that, he then led the group through the process for creating data points and plotting them over a modern map and exporting the whole thing to a PDF. Geoff also shared a number of simpler, Mac-compatible software tools that can help historians perform this task with minimal confusion while taking up less space on one’s hard drive than ArcGIS. After completing these three different workshops, I feel as though I have a better sense of how I can expect ArcGIS and other mapping software to behave. I find that if I think of ArcGIS as a series of overhead transparencies or sheets of semi-translucent graph paper, the program’s insistence on layers makes more sense. Likewise, when one considers the process of creating a paper map, beginning from an outline of a land mass, filling in areas with color, placing specific shapes, and finally adding a compass, scale, legend and title, the arrangement of the tools in ArcGIS is more intelligible. Or maybe just more sympathetic and approachable. I have a number of archival ‘spreadsheets’ that list water observations about water quality with precise locations, I plan to create some proper data sets to map in the near future. I have the enormous good luck to be studying a place that has been frequently surveyed, with many digital files readily available. The workshops have shown me how much the availability of data sets can vary, depending on the number of people researching a place and depending on the means and willingness of governments to facilitate access to these kinds of tools. Furthermore, as an historian I’ve noticed that shape-files are readily available for political boundaries that exist in the early twenty-first century in the Western Hemisphere, but remarkably scarce for all other times, even the last decades of the twentieth century. Meredith Denning is recent graduate of Georgetown University’s history PhD program. Her research focuses on the environmental and diplomatic history of Canada and the United States. In addition to her historical pursuits, she takes an interest in contemporary environmental policy and the local politics of her hometown, Toronto. She enjoys canoe tripping, bicycling, and urban gardening.

0 Comments

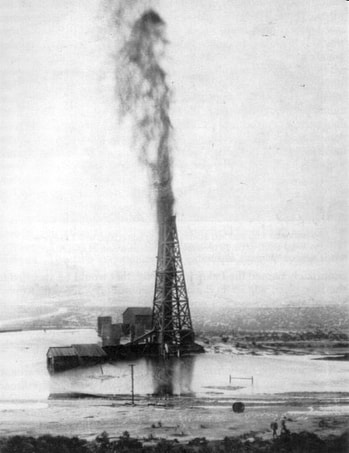

Matthew Johnson This post is part two of a field trip series where Matthew writes about his visits to raw materials extraction sites and how he understands them as an environmental historian. Read part one here. On March 15, 1910, the earth thundered underneath a crew of Union Oil geologists who were drilling for petroleum in a dusty patch of semi-arid desert and chaparral, a shrubland plant, on the southwestern edge of the San Joaquin Valley. The Lakeview No. 1 derrick rumbled and a huge column of oil and sand twenty-feet wide and two-hundred-feet tall shot into the air. The geologists had struck oil. For the next eight months, the Lakeview No. 1 gusher spewed oil uncontrolled, coating the surrounding countryside in petroleum and creating a huge lake of oil and sand at the derrick’s base that soon swallowed the derrick and drilling equipment. Workers eventually contained the lake using sandbags, but for ten more months oil continued to pour out of the well. Very little of the oil was saved and most evaporated or seeped into the ground. On September 10, 1911, the bottom of the crater caved in and the well ceased gushing oil. Workers have since filled in the crater and erected a plaque to mark the site. During the first half of the twentieth century, oil spills of such magnitude were not mourned as environmental disasters but celebrated as harbingers of oil wealth and material progress. The Lakeview gusher may have been short lived, but oil production in nearby oil fields was enduring. Lakeview No. 1 sits atop the Midway-Sunset oil field, the largest among a series of giant oil fields that were discovered in West Kern County between 1889 and 1911. The discovery of these oil fields set off a huge boom in commercial oil production that made California one of the most prolific oil producing states. In 1893, California was producing only 470,000 barrels of oil per year, but by 1910 the state was producing 73 million barrels of oil per year and its production accounted for more than one fifth of total oil production worldwide. During the following decade, California became the leading oil producer in the United States and Midway-Sunset alone was responsible for half of the state’s oil production. Oil companies erected thousands of wooden oil derricks across West Kern County and by 1923, California’s oil fields accounted for a full quarter of oil production worldwide. The Lakeview No. 1 gusher was one of the largest oil spills in the United States’ history. In eighteen months, 9.4 million barrels of oil gushed from the well, more than twice the 4.4 million barrels of oil that spilled into the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 and more than ten times the 900,000 barrels of oil spilled at Spindletop, a famous gusher in Texas, in 1901. The West Kern oil fields remain some of the most productive oil fields in the country. In 2016, California ranked third in oil producing states, behind Texas and North Dakota. Midway-Sunset is the largest oil field in California, producing 24.7 million barrels of oil in 2016. The top five oil fields in California are from West Kern County and in 2016 these five fields alone accounted for 52 percent of California’s oil production. California’s oil fields, along with other such fields across the world, revolutionized human history. Fossil fuel use facilitated unprecedented levels of population growth, urbanization, and motorization (among other things) that has reshaped how humans interact with each other and with the nonhuman world. The modern world as we know it would simply not function without petroleum. Although many recognize the essential role that petroleum plays in their lives, few have ever visited an oil field or refinery and fewer still pause to reflect on the fact that their consumption habits tie them to distant environments that produce and refine this black gold. The site of the Lakeview No. 1 gusher and the Midway-Sunset oil field are testaments to this distancing. Except for the plaque commemorating the well and the message board that recounts the site’s history, the dusty depression of the once-prolific gusher is otherwise indistinguishable from the surrounding desert. More noticeable from Highway 33 is the forest of oil pumps that stretches as far as the eye can see in some places. But I grew up in California and know few other Californians who have ever driven down highway 33 and fewer still who would recognize the name Midway-Sunset or the historical importance of the West Kern oil fields. In 2014, my family and I visited the oil fields. As I stared out the window at the industrial landscape of steel pipelines and oil pumps unfolding across the desert in front of me I struggled to reconcile how this foreign and forbidding landscape was at the heart of a standard of living I have come to take for granted. After visiting the site of the Lakeview No. 1 gusher and stopping to take photos of the Midway-Sunset oil field, we concluded our trip at the Western Kern County Oil Museum in Taft. The local chapter of the American Association of University Women established this amazing museum in 1974 when it rallied to save the last of Kern County’s wooden derricks. The site has a wealth of information about the history of the oil industry, both local and worldwide. During my childhood and adolescence, I had traveled through the San Joaquin Valley many times to visit relatives in Southern California. As our family sped down highway 5, I used to fight boredom as I stared out the window at the endless grape and almond fields. Studying environmental history has changed my comprehension of these places. As a child, I never would have imagined that just beyond the agricultural horizon (which has its own rich history) there were sites of such intrigue and importance to the energy regime of the modern world. Studying environmental history has transformed a landscape of boredom into one of endless fascination. Understanding the environmental history of a place helps make visible distant landscapes and people that are essential to maintaining a unique and unprecedented standard of living that many have come to accept as normal. Every day, thousands of people speed along Highway 5 to and from urban and suburban centers, in cars that burn oil, without a second thought to the oil fields thirty miles west that sustain their trip and the cities and suburbs they call home. The Midway-Sunset oil field, and the other coal and oil fields like it across the world, are at the very heart of modern life and it is surprising that so many people overlook them. Visiting sites of energy extraction and production while also learning about their history is an important step in reconciling the deep ambiguities and unease that characterize our relationship with fossil fuels and their impact on the nonhuman world. For more information about Californian oil history see: Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Touchstone, 1991); Paul Sabin, Crude Politics: The California Oil Market, 1900-1940 (University of California Press, 2004); and the websites for the West Kern Oil Museum, San Joaquin Valley Geology, and California Department of Conservation. Matthew Johnson is a PhD Student at Georgetown University who studies modern Latin American and Caribbean environmental history. His dissertation will look at the social and environmental costs of large hydroelectric dams built by Brazil’s military government in the 1970s and 1980s.

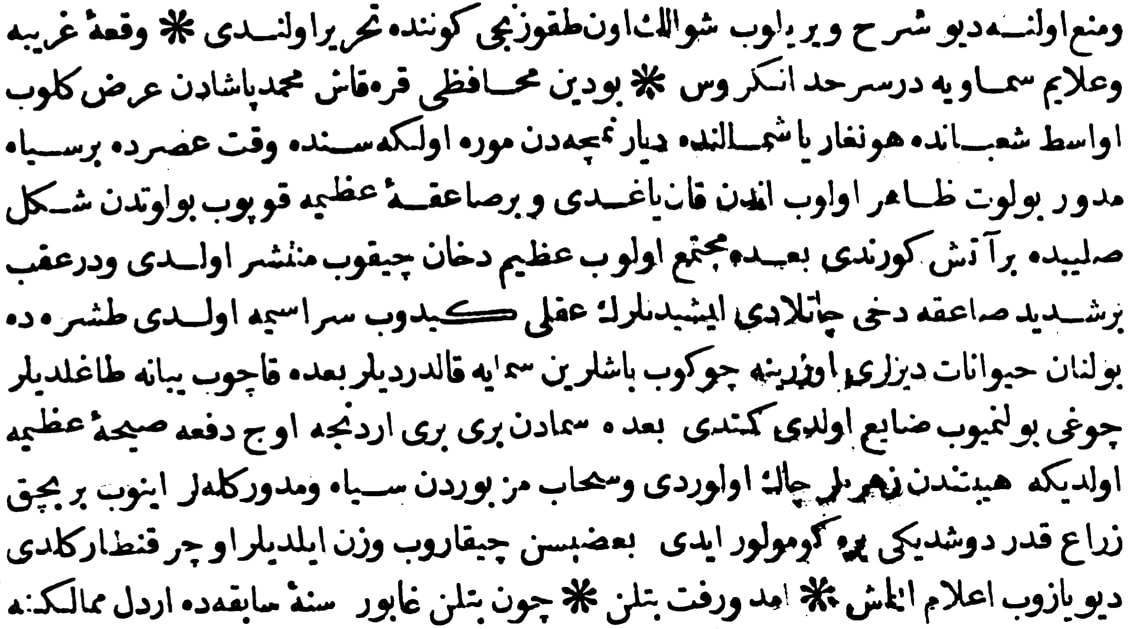

Faisal Husain Skies raining blood, clouds catching fire, and beasts running amok—a surreal mix of fact and fantasy, the kind of which only a malnourished graduate student could conjure up before drifting off to sleep in a cold, dim library. The Ottoman scholar Katib Çelebi (d. 1657) would beg to differ. The setting for these disturbing images, he reported in his chronicle Fezleke, was Hungary in late June 1619, soon after the breakout of Europe’s Thirty Years’ War. The story is loaded with enigmatic symbolism that I dare not explain, at least not today. Below is a rough translation of the Ottoman text based on the version found in Mustafa Naʿima’s (d. 1716) chronicle, whose prose in this passage is a bit clearer than Çelebi’s. A Strange Event and Celestial Signs in the Hungarian Frontier A report came from the governor of Budapest Karakaş (Black-Eyebrowed) Mehmed Pasha. One afternoon in the middle of [the month of] Shaʿban, he wrote, from the lands of Austria north of Hungary all the way to the Morea, a round black cloud emerged, from which blood rained down and a great thunderbolt erupted. Fire from the cloud in the shape of a cross appeared and later compacted. Great smoke exuded and spread. A violent thunderbolt once again burst. Those hearing were stupefied and lost their senses. Animals in the country knelt down and raised their heads to the sky, soon later running away and scattering in the wilderness. Most of them [swiftly] left and disappeared. The flowers were afterwards ripped to pieces in fear of a great cry from the sky, coming three times one after another. Round and black cannonballs came down from the aforementioned cloud, [crashing and] getting buried one and a half ziraʿ into the ground. [People] excavated and weighed some of them; each one of them was three qintar heavy. Source: Mustafa Naʿima, Tarih-i Naʿima, 2 vols. (Istanbul, 1147 AH/1734 CE), 1:326-327. We can all agree that the story doesn’t make ecological sense. The sky, needless to say, doesn’t rain cannonballs, regardless of how much they weighed. We can also agree that the mental stability of Katib Çelebi, one of the most accomplished Ottoman intellectuals of his time, is beyond question. If our premise is true, what do you make of the story? Faisal Husain is a doctoral candidate at Georgetown University’s Department of History. He recently defended his dissertation, “The Tigris-Euphrates Basin Under Early Modern Ottoman Rule, c. 1534-1830.” Jackson Perry The modern history of the ‘discovery’ of Australia typically reads as a tale of the wider world coming to the island continent, in such diverse forms as European colonists and prisoners, rabbits, California redwoods, infectious diseases, and common law. Less emphasized in this tale is the Australian contribution to the history of other parts of the world. For environmental historians and historians of science in particular, there is no better place to understand that contribution than the library of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne. I visited Melbourne in the winter of 2016 (the southern hemisphere’s winter, that is) seeking primary sources on the spread of eucalyptus to the Mediterranean region in the 19th century. Thanks to the generous support of the Cosmos Club of DC Foundation, I spent two months immersed in the physical and literary world of the German-Australian botanist Ferdinand von Mueller (1825-1896). Mueller immigrated to Australia in 1848, taking the helm of the Melbourne gardens nine years later. Over the next four decades, he engaged in a staggeringly rich correspondence from the edge of the British Empire with the world’s scientific elite, including the Hookers of Kew, Darwin, Agardh, Gray and Liebig, as well as lesser known practitioners of science on every continent. Much of that correspondence was lost after his death; several thousand letters have been reassembled, translated, and made available for researchers in Melbourne. For my purposes, Mueller's interactions with the Mediterranean world included frequent dispatches of eucalyptus seeds to Algeria, France and Italy, and interchanges of scientific information, in both private letters and published journals, with institutions of science. Scholars of North Africa will find complete runs of the Bulletin de la Société d’Agriculture d’Alger (image, right) and the Bulletin Agricole de l’Algérie-Tunisie-Maroc, alongside mycology journals and numerous volumes of Linnaean societies from across the European continent. Other topics with rich potential for further study include the social and bureaucratic histories of pre-Federation Australia, the exploration of Australia, Oceania and the Antarctic, networks of exchange in the Indian Ocean and the British Empire, German colonialism in Africa and Australasia, and Mueller's engagement with the theory of evolution. Further reading:

Jackson Perry is a PhD candidate in history at Georgetown University who studies the transformation of modern Mediterranean environments. His dissertation examines the introduction of the Eucalyptus tree genus to the Mediterranean region in the nineteenth century. Matthew Johnson This post is part two of a field trip series where Matthew writes about his visits to raw materials extraction sites and how he understands them as an environmental historian. Read part two here. In the 1850s, Californians experienced the state’s natural environment primarily through work. In was the gold rush then and the northern Sierra Nevada foothills were overrun with miners. Although many Californians associate gold mining with human labor, the largest and most productive companies harnessed the mountain’s rivers to mine for gold. Mining companies built networks of reservoirs and canals that diverted water to hydraulic cannons which then blasted the water against mountainsides. As entire hillsides washed away, a mercury-lined sieve sitting in the center of the valley attracted gold. By the mid-1870s, a hydraulic mine at North Bloomfield, near present day Nevada City, became the largest gold mine in the state. The landscape at North Bloomfield was so scarred from the water cannons that French miners reportedly compared it to the Battle of Malakoff, a bloody episode in the Crimean War (1853-1856). Historian Andrew Isenberg argues that hydraulic gold mining had a staggering environmental cost and encouraged a host of other industries such as logging, ranching, and urban growth, which also degraded the nonhuman environment. In the 1850s and 1860s, the government overlooked such costs because gold mining was lucrative. However, in the 1870s and 1880s, a coalition of farmers and railroads helped pass legislation that put a stop to hydraulic mining, which was sending torrents of mercury-infused sediments downstream to inundate fields. In 1884, California courts banned hydraulic mining because of its environmental impact and the North Bloomfield mine closed shortly thereafter. In 1965, roughly a century later, the government declared the old gold mine a state park. The transition from North Bloomfield gold mine to Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park reflected a change in how many Californians were experiencing nature. Like many urban Californians, I’ve experienced the Sierra Nevada primarily through play. Though nature remains an essential part of urban living, since the second industrial revolution the relationship has become increasingly indirect and less visible. For many, though certainly not all, urbanites, direct experiences with nonhuman landscapes are increasingly relegated to the realm of leisure. Historians Richard White and William Cronon argue that a major shortcoming of modern environmentalism is that its proponents interact with nature at a distance, through contemplation and eyesight, and don’t recognize that historically humans have known nature through work. This outlook has encouraged environmentalists to value uninhabited areas far removed from our homes and does not teach us how to better manage the parts of the nonhuman world we do inhabit and use as resources. Last summer I spent time with family and friends hiking and swimming in the Sierra Nevada. Having read about North Bloomfield, I lobbied to stop, and after winding our way through empty mountain roads we arrived at the ghost town. We checked in at the museum, and then proceeded to the ‘diggins.’ I spent over an hour hiking the perimeter of the old gold mine, staring at the weathered cliffs and struggling to imagine how the lush fields I walked through were once hills themselves, and then briefly a watery mess of mud and mercury that quickly disappeared downstream. Environmental history has given me an appreciation of such sites. Unlike the reservoirs, oilfields, power stations, and landfills I’ve visited, North Bloomfield has no direct connection to my life. Yet, shortly after California’s birth as a U.S. state, it was the center of the state’s most lucrative industry, which attracted capital and immigrants and encouraged commerce and urbanization in Sacramento and the Bay Area. Studying environmental history has not changed the fundamental parameters of my relationship with the natural world: my direct experiences with nature remain primarily leisure-based. But it has given me a greater appreciation for just how strange such a relationship is in the long sweep of human history. As I walked through the gravely remains of the North Bloomfield mine, stopping to take photos, I reflected on how utterly different my experience of this space was than those who used it before me. For more information see: Andrew Isenberg. Mining California: An Ecological History. NewYork: Hill and Wang, 2005 and William Cronon. Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1996. Matthew Johnson is a PhD Student at Georgetown University who studies modern Latin American and Caribbean environmental history. His dissertation will look at the social and environmental costs of large hydroelectric dams built by Brazil’s military government in the 1970s and 1980s.

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed