|

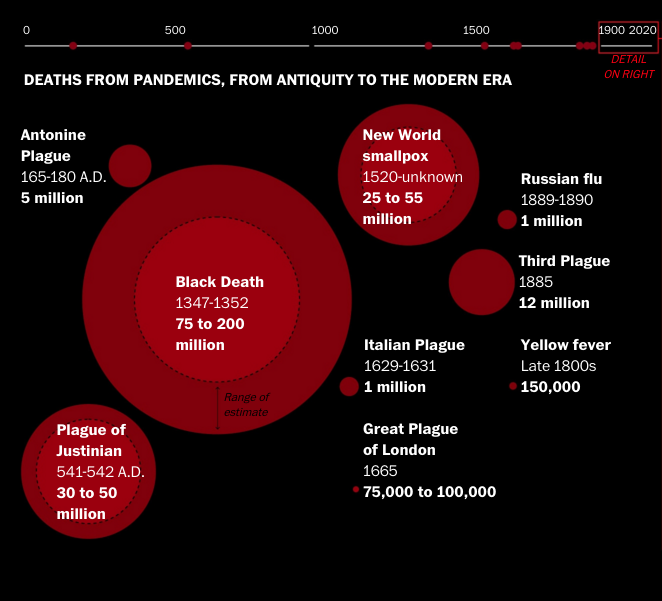

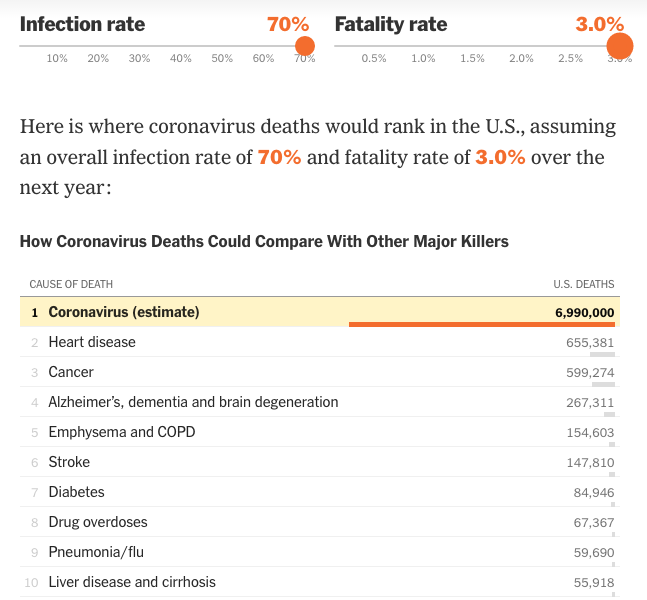

Tim Newfield Another day, another spillover. Is history repeating itself? Sure, in some respects, but no, not really. Novel human diseases may emerge every year, but not like this. SARS-CoV-2 has pulled off what countless other pathogens have failed to: it’s globalized and become endemic. Sequence data indicates that the spillover happened in late November (1). Since then well over four million confirmed cases and 290,000 deaths have been reported in more than 215 countries and territories. Worse yet, it is next to certain that millions of more COVID-19 cases (severe, moderate, mild and asymptomatic) have gone unconfirmed and that official tallies omit tens of thousands of lives lost to COVID-19. A large percentage of the world’s population has been in “lockdown” for weeks. The first wave is ongoing in some regions; in others the second has begun. Months into the pandemic, it’s starting to sink in that this disease isn’t going anywhere soon if at all. This is a crisis unlike any other. That’s not to say it’s worse than any other novel disease emergence. It’s not. SARS-CoV-2 has nothing on the great influenza (1917-20) or the Black Death (1346-52), let alone smallpox or measles, which spilled over once too. A number of other old diseases (like malaria and tuberculosis to name but two) likewise make the current outbreak seem insignificant, but of course it’s not. The numbers make that clear. It has been, and will continue to be for some time, a public health crisis and a source of considerable tragedy. It’s not insignificant, it’s just different. That hasn’t always been clear in COVID-19 coverage, however, and not drawing attention to everything that separates our current pandemic from those of the past may have come at a cost.  Tionfo della morte, Pisa, fresco, mid-fourteenth century. Bodies of secular and religious elites, women and men, heaped in a mass grave. Death harvests above. Long thought painted shortly after the Black Death by Agnolo Gaddi or Francesco Traini, more recently attributed to the obscure Buonamico Buffalmacco and dated to c.1335-40. The Black Death and the current coronavirus pandemic are worlds apart. Courtesy of the author. Epidemiologists say “if you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic”. Historians and journalists would do well to adopt the same mantra. No two diseases nor any two moments in time are the same. Different as it may be, SARS-CoV-2 is going to leave a perceptible mark on history, like other pandemics have. There is talk already of life before and life after this pandemic. Things will change, we’re told. Whether they change for the better or not, a myriad of impacts, big and small, stemming from the outbreak and the lockdown will be visible years down the line when historians look back. But what should historians do now? Can the stewards of the past contribute in meaningful ways as the disease continues to spread? These are tricky questions. It’s not the business of history, after all, to curb disease outbreaks or to forecast what lies ahead. Serial intervals, infection rates, and reproduction numbers are not the bread and butter of history. Predicting what would or will happen has proved tough for even the most experienced of epidemiologists. So, historians should probably do something else. Lessons from the past, it has been said (2), normally come from outside the discipline of history, but there’s been no shortage recently of historians willing to draw linkages between the present and what’s come before. Journalists have had a field day with history too. If pseudo-epidemiology has grown exponentially in recent months, the number of practicing armchair historians at present has broken with all precedent. Historians, of course, could put things in context. They could help us understand how it is that we ended up here, an essential step in making sure we don’t stay here. There’s no shortage of topics. In some respects, it all matters, from globalization and urbanization, to public health preparedness and the rise and reach of health internationals, to climate change and our exploitation of animals and ecosystems. These big subjects are just a start. Historians should also be in the business of drawing a hard line between present and past pandemics. I’ve found many of the history lessons, by and largely given by journalists, in the context of the current pandemic hard to stomach. Most are underdeveloped. This isn’t surprising, as newspapers and blogs have word limits (I’ve already spent a third my allowance), but the simplification those mediums require can deteriorate quickly. Before you know it, something’s been oversimplified, anachronism’s been committed, and both the present and the past have been misrepresented. The lessons are also hard to stomach because they imply or assume that our diseased present and some diseased past are commensurate. They suggest that what we’re living through has been lived through before. That is, that we haven’t paid enough attention to the past or recognized our mistakes. To some extent, this is, of course, the case. Pandemics aren’t new and spillovers are common. Sadly, xenophobia, racism and disease also have a long history. Lockdowns, quarantines, social distancing, they’re all old news too. There’s no novelty in the mad race for a vaccine either and powers that be have been seizing upon epidemics to push their agendas for centuries. The fatness of one’s wallet has as well always mattered in the face of a disease outbreak and I doubt there have been many epidemics that haven’t intensified socio-cultural anxieties, racial and geographical privileges, and economic disparities. Ok, but while there is no shortage of parallels to uncover, it’s certainly true that we have to ignore a lot to find them. If the oversimplifying weren’t bad enough, the straightforward lessons (and warnings) don’t seem to be working. This isn’t the first time historians, armchair or not, have jogged our memory about these things, after all. During (and after) the 2013-15 Ebola epidemic, the 2009 influenza pandemic, or the 2003 SARS outbreak, for instance, we heard much the same (though perhaps less often). As valuable as these unheeded lessons might be (or could be if we actually acted on them), that they almost always come from some great historical plague is, to my mind, a real problem. Drawing lines between the great influenza or the Black Death and SARS-CoV-2 implies that our current crisis is on par with the largest, most significant disease outbreaks of history. As early as January 25th (3), the U.S. paper-of-record, the New York Times, was drawing linkages between the current pandemic and that which was wrapping up about this time a century ago, the great influenza. They did so again on 1 February (4). At that time, fewer than 15,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 300 deaths had been reported. By March 1st, the NYT had linked COVID-19 with the great influenza in no fewer than 17 articles (5). On February 27th, the same paper began drawing the same linkage on their podcast The Daily. That day, their guest, the NYT’s own resident ‘plagues and pestilences’ journalist, expressed concern about being “too alarmist”, but he didn’t hesitate to claim “this one”, that is the COVID-19 outbreak, “reminds me of what I have read about the 1918 Spanish influenza” (6). Associations in COVID-19 coverage, usually quick and flippant, with truly great plagues, like the century-old influenza pandemic, accumulated in no time. By mid-March the Black Death started gaining traction. The most infamous later outbreaks of the second plague pandemic, the 1665-66 plague of London and 1720-22 Provençal Peste (or plague of Marseille), also eventually got their due. I knew journalists were digging deep when I started encountering references to the more obscure Antonine and Justinianic plagues of the second and sixth centuries. Less surprising, Thucydides’ better-known Athenian plague also went viral. I’d be contradicting myself if I said these connections were absurd – as noted, historians aren’t in the business of predicting the future and SARS-CoV-2 isn’t over – but these connections were as absurd then as they are now. It’s been clear for months that COVID-19 is not going to rank among the greatest pandemics of history. This may be hard to hear, or seem improbable, considering the scale and duration of the global lockdown and that millions have been infected and hundreds of thousands killed, but it’s not on par with the great influenza let alone the great plagues of premodernity. There are countless reasons for this. We might start with the fact that it’s hard to be a premodern plague in 2020. But even if we were living in 165, 541 or 1346, the current pandemic wouldn’t be one of the great plagues. In fact, had SARS-CoV-19 spilled over then, it wouldn’t have made history.  Infographic from M. Rosenwald, “History’s deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America” Washington Post 7 April 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/local/retropolis/coronavirus-deadliest-pandemics/ There are too many issues with this figure to discuss here. A few: even rough mortality estimates for the Antonine and Justinianic plagues are suspect. Some question whether the Antonine plague was a singular disease outbreak, let alone one of pandemic scale. That 50 million might have died in the Justinianic plague is an absurd claim considering the evidence at hand. At the same time, some historians have argued the ‘Italian plague’ of 1629-31 killed twice the number listed here. That the Black Death claimed upwards of 200 million lives is hard to make sense of. Although the Black Death has suffered for more than a century from extreme Eurocentrism, recent scholarship has emphasized that the great mid-fourteenth-century pandemic spread widely and killed millions in southwest Asia and North Africa, and that it possibly disseminated across large areas of Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa too. Perhaps the total mortality surpassed 100 million, but that is as far from certain as you can get, particularly if the pandemic is fixed the standard European dates of 1347-52. (7) Using the past to sensationalize the present helps attract and maintain readers, I have no doubt. Disease history sells, even when we aren’t living through a pandemic. But could connecting the present outbreak to the biggest plagues on record come at a cost? No matter how casual or careless the connection, one might think repeatedly putting SARS-CoV-2 side-by-side with the great influenza or the Black Death has the capacity to do harm. Misusing history in this way might affect the mental health of millions of readers. I’d say this is all the more likely if most readers know great historical plagues only vaguely as major, world-changing events, that is, if they aren’t ready with all the stats they need to understand how ludicrous the connections are. Ties to the great plagues of old, whether they’re meant to teach something or not, could unnecessarily cause or aggravate anxiety and fear. They could help whip up panic. I’d like to think these linkages to past plagues were (and are still) intended to encourage social distancing – as in bad history done purposefully to frighten people to do what’s right: stay inside, break chains of transmission and protect the most vulnerable. But I’m not so sure. Fear sells and considering how many reports there have been playing up this novel coronavirus’ “mysterious origins”, “freak mutations” (8), and seemingly shifting symptomatology, I don’t think history has been deliberately played with for the sake of the greater good. If fear didn’t sell, worse case scenarios (9), and all the unknown variables imaginable wouldn’t steal the bulk of the headlines. To give but a single example: Well after the NYT cemented their connection between COVID-19 and the great influenza, they published an online article in mid-March with a ‘range slider bar’ that allowed readers to play with population infection and case fatality rates and to forecast by themselves what was to come. This was thoughtless pseudo-epidemiology at best. If one maxed out the infection rate bar at 70 percent and the fatality rate bar at three percent, as anyone would, they learned nearly seven million Americans were going to die (10). This is but one example. There are many, many more. That we were told early on in the NYT to “go medieval” (11) on the “Wuhan” or “Chinese” virus (12), might have tipped us off that the past was going to be used carelessly in the media and that important earlier lessons, about xenophobia, racism and fixing geographic labels to pathogens for instance, were going to be ignored in COVID-19 coverage. Historians have been helping to set things straight (13), but ideally they would fact check the fact checkers, as it were, in the very same outlets and reach the same large, nonacademic audience. But bringing the crisis down to size risks discouraging people from doing what they need to do. It could be counterproductive to point out that no fewer than 675,000 Americans died in the three waves of influenza that passed through the country in 1918-19, and that that’s about 2.3 million deaths if we multiply to reflect today’s population size, or that no historian thinks fewer than ten million people died in India during that century-old pandemic – the equivalent of well more than 45 million deaths now. That the Black Death claimed tens of millions of lives in the wider Mediterranean region and Europe, perhaps 45 percent of the total affected population, in just a few years, halved the populations of countless cities in mere months, and spread and killed far more widely yet, makes our current crisis look even smaller. Bringing the crisis down to size isn’t going to persuade people to do what they should. Historians have much to do, but they walk a fine line if they undercut misleading linkages with past plagues – that undercutting risks disrespecting the gravity of the crisis for those affected and those most at risk. It could also hurt our best efforts to mitigate the pandemic. References (1) K. Anderson et al, “The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2” Nature Medicine 26 (2020), pp. 450-452. (2) R. Peckham, “COVID-19 and the anti-lessons of history” The Lancet 395 (2020), pp. P850-852, but do read A. White, “Historical linkages: epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia” The Lancet 395 (2020), pp. P1250-1251, C. Ermus, “The danger of prioritizing politics and economics during the coronavirus outbreak” Washington Post 13 March 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/13/danger-prioritizing-politics-economics-during-coronavirus-outbreak/ (3) D. Grady, “Chicago woman is second case to be confirmed in the U.S., the C.D.C. says” NYT 25 January 2020, A8. There were 1,320 confirmed cases at the time. Perhaps it should be said that the NYT is one of only three papers I read regularly. I have yet to review my notes on the other two. (4) D. Grady, C. Rabin, “C.D.C. imposes 2-week quarantine on evacuees from Wuhan” NYT 1 February 2020, A11. (5) D. Grady, “Chicago woman is second case to be confirmed in the U.S., the C.D.C. says” NYT 25 January 2020, A8; D. Grady, C. Rabin, “C.D.C. imposes 2-week quarantine on evacuees from Wuhan” NYT 1 February 2020, A11; D. McNeil Jr., “Rise in cases suggests epidemic is pandemic” NYT 3 February 2020, A12; R. Rabin, “A deadly new contagion” NYT 4 February 2020, D1; A. Qin et al, “Beijing imposes extreme limits on ill in Wuhan” NYT 7 February 2020, A1; R. Gladstone, “As Chinese grapple with a new illness, an old stigma is revived” NYT 11 February 2020, A11; R. Rabin, “Warehousing patients also has its hazards” NYT 12 February 2020, A8; M. Richtel, “Getting online keeps lives on track for those in quarantine” NYT 19 February 2020, A8; R. Rabin, “Scientists study why the illness seems to be hitting men harder than women” NYT 21 February 2020, A7; F. Stockman, L. Keene, “In California, the quest for a new quarantine site sets off a rare legal battle” NYT 25 February 2020, A9; M. Osterholm and M. Olshaker, “How to mitigate the impact of the coronavirus” NYT 25 February 2020, A27; J. Goldstein and J. Mckinley, “Stockpiling supplies and working through outbreak scenarios” NYT 28 February 2020, A23; P. Krugman, “Pandemic, meet the Trump personality cult” NYT 28 February 2020, A25; D. McNeil Jr, “Censorship is never the best medicine in an epidemic” NYT 29 February 2020, A15; D. Phillipps, “U.S. military prepares plans to battle an invisible enemy” NYT 1 March 2020, A27; D. McNeill Jr., “To take on the coronavirus, go medieval on it” NYT 1 March 2020, SR3; N. Kristof, “Is this ‘the big one’?” NYT 1 March 2020, SR11. (6) “The coronavirus goes global” The Daily 27 February 2020, 03:06-04:46. Everyone should know by now that there wasn’t much particularly ‘Spanish’ about the 1917-20 influenza pandemic other than that in the West it was reported early on in Spain, a neutral country in WWI and without wartime censorship. (7) L. Mordechai et al, “The Justinianic plague: an inconsequential pandemic?” PNAS 116 (2019), pp. 25546-25554; N. Varık, Plague and empire in the early modern Mediterranean world: the Ottoman experience, 1347-1600 (CUP, 2015); M. Green, “Putting Africa on the Black Death map: narratives from genetics and history” Afriques 9 (2018), doi.org/10.4000/afriques.2125; T. Brook, Great state: China and the world (Profile Books Ltd, 2019); H. Barker, “Laying the corpses to rest: grain embargoes and the early transmission of the Black Death in the Black Sea, 1346-1347” Speculum, forthcoming. (8) D. McNeil Jr, “Rise in cases suggests epidemic is pandemic” NYT 3 February 2020, A12; idem, “What the next year (or two) may look like” NYT 19 April 2020, A1. J. Corum and C. Zimmer, “How coronavirus mutates and spreads” NYT 30 April 2020 should be read alongside N. Grubaugh et al, “We shouldn’t worry when a virus mutates during disease outbreaks” Nature Microbiology 5 (2020), pp. 529-530. The inclusion of the remarks of Dr. S. Bell in C. Zimmer, “On the trail of New York’s Covid-19 cases” NYT 14 April 2020, D7, is to be noted. (9) C. Zimmer, “2 scenarios for Covid-19: best and worst” NYT 22 March 2020, SR2. (10) J. Katz, “Could coronavirus cause as many deaths as cancer in the U.S.? Putting estimates in context” NYT 16 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/16/upshot/coronavirus-best-worst-death-toll-scenario.html) (11) D. McNeill Jr., “To take on the coronavirus, go medieval on it” NYT 1 March 2020, SR3. (12) In late January and early February, the NYT referred to “Wuhan virus”, “Wuhan coronavirus”, “Wuhan strain,”, “Chinese virus”, “China virus” in no fewer than 17 articles: R. Rabin, “First patient with the mysterious illness is identified in the U.S.” NYT 22 January 2020, A10; D. Grady, “As new virus spreads from China, specialists see grim reminders” NYT 23 January 2020, A8; A. Qin and V. Wang, “China closes off city at center of virus outbreak” NYT 23 January 2020, A1; Y. Huang, “Is China setting itself up for another epidemic?” NYT 23 January 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/opinion/coronavirus-china-wuhan.html; M. Baker, “Texas student is monitored after a trip” NYT 24 January 2020, A7; D. Grady, “Chicago woman is second case to be confirmed in the U.S., the C.D.C. says” NYT 25 January 2020, A8; M. Baker and J. Singer, “Chinese-Americans feel glare and rush to help” NYT 25 January 2020, A8; J. Gorman, “They are mammals, they fly and they host pathogens” NYT 29 January 2020, A7; R. Rabin, “Beijing says expert teams are welcome” NYT 29 January 2020, A7; D. Grady, “Outside China, racing to halt virus’s spread” NYT 30 January 2020, A1; A. Stevenson, “Borders sealed and flights banned as world works to contain virus” NYT 2 February 2020, A11; D. McNeil Jr., “Rise in cases suggests epidemic is pandemic” NYT 3 February 2020, A12; R. Rabin, “A deadly new contagion” NYT 4 February 2020, D1; R. Rabin, “Experts fear patients spreading virus even without signs of symptoms” NYT 5 February 2020, A9; C. Krauss, “Virus threatens an oil industry that’s already ailing” NYT 5 February 2020, B1; A. Harmon, “Inside the race to contain America’s first confirmed case” NYT 6 February 2020, A6; C. Buckley, “Whistle-blower on China virus succumbs to it” NYT 7 February 2020, A1. But also see: M. Rich, “Virus fuels anti-Chinese sentiment overseas” NYT 31 January 2020, A1, and notably, L. Yi-Zheng, “The coronavirus and ‘jinbu’ foods” NYT 23 February 2020, SR2. For an earlier “China virus” in the NYT: A. Jacobs, “China virus kills 22 and sickens thousands” NYT 3 May 2008, A6. (13) A few examples: J. Crawshaw, “Quarantine – an early modern approach” History & Policy 12 March 2020, http://www.historyandpolicy.org/opinion-articles/articles/quarantine-an-early-modern-approach; M. Bresalier, “Covid-19 and the 1918 ‘Spanish flu’: differences give us a measure of hope” History & Policy 2 April 2020; M. Zuk and S. Jones, “Covid-19 is not your great-grandfather’s flu – comparisons with 1918 are overblown” Greenly Tribune 23 April 2020 https://www.greeleytribune.com/opinion/marlene-zuk-and-susan-d-jones-covid-19-is-not-your-great-grandfathers-flu-comparisons-with-1918-are-overblown/; G. Geltner, “Getting medieval on Covid? The risks of periodizing public health” History News Network 29 March 2020, http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/174758; N. Varlık with C. Horn, “Covid-10 impact: the history of plague and contagion” University of South Carolina, https://www.sc.edu/uofsc/posts/2020/03/covid_impact_nukhet_varlik.php#.Xrne9yMrJjc; T. Brook, “Blame China? Outbreak orientalis, from the plague to coronavirus” The Globe and Mail 13 February 2020, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-outbreak-orientalism-from-the-plague-to-coronavirus-why-is-the-west/; A. Heinrich, “Before coronavirus, China was falsely blamed for spreading smallpox. Racism played a role then, too” The Conversation 6 May 2020, https://theconversation.com/before-coronavirus-china-was-falsely-blamed-for-spreading-smallpox-racism-played-a-role-then-too-137884. Cf. G. Kolata, “Coronavirus is very different from the Spanish flu of 1918. Here’s how” NYT 9 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/health/coronavirus-is-very-different-from-the-spanish-flu-of-1918-heres-how.html/ Dr. Tim Newfield is an Assistant Professor in History and Biology at Georgetown. He is an environmental historian and historical epidemiologist, and he regularly leads seminars on global infectious disease history.

1 Comment

Graham Pitts In 2011, I visited Lebanon’s Shouf Biosphere Reserve to see what I could discover about the history of the country’s forests. Located on the slopes of the Barouk range of the Lebanese mountains, the reserve covers five percent of the national territory. Conservation efforts are primarily directed at preserving the national emblem, the cedars of Lebanon (cedrus libani). The tree’s broad, irregular branches distinguish it from other conifers. No one I asked, nor anything I read, could say with precision when Lebanon’s forest cover dwindled to the 17 square kilometers of cedar forest that remain. A general sense that it had been the victim of “centuries of human depredation” still prevails. The limited pollen studies that have probed Lebanon’s historical flora do not substantiate such a linear relationship between humans and the rest of the environment, however. Lebanon’s forests thrived despite climactic variations of the previous several millennia. My research suggests that human activity did not severely threaten the extent of forest cover until the mid-nineteenth century when a burgeoning silk industry relied on wood fuel to power steam-driven looms. By the end of the century, Lebanon’s forests were devastated. Today, climate change poses a potentially existential threat to the Shouf’s remaining cedars. Seated in an old house in the town of Maaser El Shouf, beside a traditional wood-burning stove, I asked the Biosphere’s director Nizar Hani about the history of deforestation and conservation. Hani was eager to discuss the Biosphere’s efforts to save them. The reserve was created in 1996, when several villages had donated a portion of their communal lands that were included along with state-owned land. How had this public-private partnership resulted in the most substantial conservation effort in the country’s history? For him the answer to that question could be found in Lebanon’s religious heritage and, in particular, the beliefs of a religious sect centered in Shouf mountains. “The Druze have a special relationship with the environment,” Hani told me. A heterodox offshoot of Ismaili Shi‘ite Islam, the Druze faith emerged in the early eleventh century. Initially associated with the ruler of Fatimid Egypt, al-Hakim, the faith only gained significant numbers of converts in modern-day Lebanon. Druze religious authorities conceal their holy texts and precise religious beliefs from outsiders and even members of their own community who are not initiated in the faith. Some attribute the sect’s interest in the environment to a belief that Druze souls will be reincarnated and therefore have a material interest in sustainability. The research fellowship I hold at Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies has given me the chance to test Hani’s argument to assess whether or not there has been something peculiar about Druze environmental history. In what sense do the Druze have a special relationship with nature? Understandings of Druze history generally highlight one defining historical characteristic: a commitment to maintaining autonomy and resisting outside authority. Druze bravery on the battlefield is a corollary to this understanding of the group’s identity. What enabled the Druze to resist the imposition of outside authority? Was it the fact that they had a particular relationship with the environment that distinguished it from the rest of the population of Mount Lebanon? While it is clear that the Druze have consistently been able to resist outside authority since the early modern period, we cannot assume—in a scholarly context—that the ability to maintain autonomy results from some kind of innate cultural or (much less) racial proclivity for freedom. What the historical conditions enabled successive the Druze to maintain relative autonomy? Beginning in the late eighteenth century, Druze peasants began to leave Mount Lebanon for the Hauran region of the Syrian interior. Deep volcanic soils there were apt for extensive grain production in contrast to the well-watered slopes of Mount Lebanon where intensive cultivation prevailed. By the mid-nineteenth century, Druze communities dominated the Hauran plain and controlled an important piece of the regional grain economy. Meanwhile, the Christian population of Mount Lebanon was increasingly reliant on the export of silk to France. Later, migration to the Americas became a solution to demographic instability. The Druze experience was distinct from the rest of Lebanon in the sense that they coped with the instabilities of industrial capitalism by seeking refuge in the production of food crops and sought the isolation of the easily defensible region that became known as the “Druze mountain”; meanwhile the rest of Lebanon relied on fickle global markets. That contrast accounts for the Druze ability to maintain relative ecological autonomy for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In that regard, I found some evidence to corroborate Hani’s idea that there is something distinctive about the Druze relationship with the environment. Recent events, especially the inability of Druze militias to stand up to Hezbollah in 2008, suggest that Druze ecological autonomy--at least in the military sense--may be a thing of the past. Today, Lebanon’s religious communities face an uncertain future together. If anything, the system that links political representation with sectarian identity in Lebanon has been a major source of corruption. Bad government is the major obstacle to the preservation of Lebanon’s rich environmental heritage. Pollution is a major factor stirring the current unrest in the country. Air quality in Lebanon is poor. Cancer rates are high. While the macro trends of the global environment, especially climate change, are far out of anyone in Lebanon’s control, local adaptations will be key in dictating the country’s future direction. Projects such as the Shouf Biosphere offer hope that the political will to cultivate a sustainable relationship with the environment exists and the current protests suggest that there is fertile soil for an environmental movement to flourish. Dr. Graham Auman Pitts is the American Druze Foundation fellow in the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies. He trained as an environmental historian of the Middle East in Georgetown’s history department. This blog post previews his work on Lebanon’s environmental history and the Druze. References

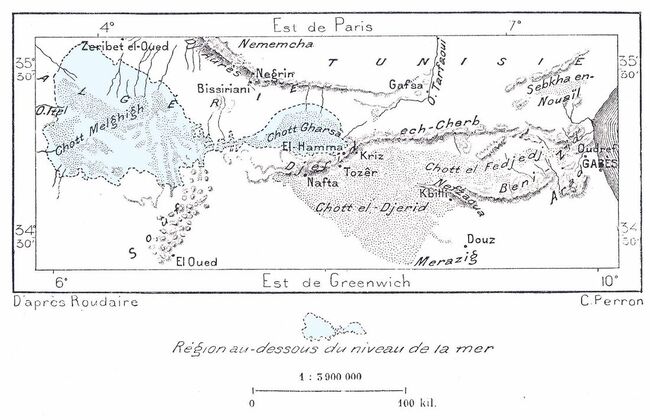

Barnard, Anne. “Climate Change Is Killing the Cedars of Lebanon.” The New York Times 18 July 2018. Cheddadi, R. and C. Khater. "Climate Change Since the Last Glacial Period in Lebanon and the Persistence of Mediterranean Species." Quaternary Science Reviews 150 (2016): 146-157. Firro, Kais. A History of the Druzes. Leiden: Brill, 1992. Pitts, Graham Auman. “The Ecology of Migration: Remittances in World War I Mount Lebanon.” Arab Studies Journal 26, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 100-127. “Fallow Fields: Famine and the Making of Lebanon.” PhD dissertation, Georgetown University, 2016. Jackson R. Perry Captain François Roudaire (1836-1885) was convinced that a large inland sea could be created in the Sahara Desert across southeastern Algeria and southern Tunisia. The French military surveyor received funding from public and private sources in the 1870s to carry out feasibility studies on that region’s chotts or shebkas, seasonal salt lakes that are sometimes found below sea level. The centerpiece of his proposal was a long canal from Tunisia’s coast on the Gulf of Gabes to low-lying chotts in the interior. Once the Mediterranean began to flow into the desert, Roudaire believed, the Saharan climate would become cooler and the rate of precipitation in the region would increase. His announcement in the widely-read Parisian periodical Revue des deux Mondes on May 15, 1874 that French engineers could build “une mer intérieure en Algérie” stirred up the imaginations of the capital’s political, social, and scientific elite. Ferdinand de Lesseps, whose success in the Suez Canal project led him to seek similarly grandiose opportunities to remake the world (e.g. in Panama), soon joined the project and helped with funding. Roudaire’s most prominent critic was Ernest Cosson, a senior member of the Société botanique de France and an expert on North African botany. Cosson and many of his colleagues in metropolitan scientific associations rejected the plan for several reasons: its clearly negative consequences of an infusion of salt water for native flora (particularly the date trees on which Saharan oasis agriculture depended); the engineering nightmare posed by a canal up to 150 miles in length; the highly questionable nature of Roudaire’s claims about climatic change; and the social unrest that would have followed the substantial expropriation of native land. The scientific community’s dismissal of the scheme, the state’s loss of interest when the difficulty of the project became clear, and the deaths of Roudaire in 1885 and de Lesseps in 1894 ended the Saharan Sea project. However, the Saharan Sea dream has lived on. In fiction, it first appeared in British journalist Louis Tracy’s futuristic An American Emperor: The Story of the Fourth Empire of France (serialized in Pearson’s Weekly, 1896-97), which features an immensely wealthy American businessman who arrives in Paris intent on making the inland sea a reality. Jules Verne’s L’Invasion de la mer (1905) describes a future conflict between colonizers attempting to build the sea and native Saharans who opposed the European effort. In Verne’s story, an earthquake that occurs at the climax of the tale causes the Mediterranean to engulf the chotts of the Sahara ahead of schedule. Several historians have already ably examined the scheme as it relates to the history of European imperialism in Africa and the history of European understandings of desertification and geo-engineering (See suggestions for further reading below). What I find illuminating in the Roudaire affair is the important role of newspapers and journals. The power of popular media to drive scientific inquiry has become quite clear in my dissertation on another ecological modification scheme of the late 19th century: the dissemination of the Australian eucalyptus tree to malarial environments in the Mediterranean, South Africa, India, and elsewhere. “The Age of Steam and Print,” as James Gelvin and Nile Green have dubbed the late 19th century, was a golden age of media frenzies and of international searches for the filler material that we sometimes call clickbait today. The newly cheap cost of printing in the 19th century, the revolutions in transportation and communication technology that enabled interesting stories to spread across national borders and oceans, and the competitive business environment of journalism, created strong incentives for editors and writers to prioritize quantity over quality, and to put fascination ahead of verification. The fantasy that Roudaire started in the Revue des deux Mondes, a popular avenue around the gatekeepers who controlled the publications of the traditional scientific societies, spread quickly throughout the European and American presses. Editors happily built the canals for Roudaire’s Saharan Sea dream to invade their empty column inches. “As it is today,” Hocine Bendjoudi and René Létolle wrote about the Roudaire episode, "journalists lacking copy periodically revived the affair in the opinion press." The dream of creating a Saharan Sea still has clickbait value today. Numerous videos on Youtube, and articles in Conde Nast Traveler, Big Think, and Gizmodo under its ’Secret History’ tag, rehash previous work on the Roudaire scheme and its intellectual successors. The basis of European conceptions of the central Sahara changed from ignorance to fascination in the era of Roudaire, Philip Lehmann argues, and there it remains today. In our modern media environment, ridiculous schemes have lives of their own, periodically entertaining audiences for years and entrenching warped understandings of the desert as a vacant land awaiting improvement. Citations and recommendations for further reading: -Diana K. Davis, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016). -Michael Heffernan, “Bringing the Desert to Bloom: French Ambitions in the Sahara Desert During the Late Nineteenth Century - The Strange Case of ‘la mer intérieure,’” in Water, Engineering, and Landscape: Water Control and Landscape Transformation in the Modern Period, 94-114, edited by Denis E. Cosgrove and Geoffrey E. Petts (London: Belhaven Press, 1990). -Meredith McKittrick, "An Empire of Rivers: The Scheme to Flood the Kalahari, 1919–1945", Journal of Southern African Studies 41, n. 3 (2015): 485-504. -Philipp Lehmann, “Changing Climates: Deserts, Desiccation, and the Rise of Climate Engineering 1870-1950,” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2014). -René Létolle and Hocine Bendjoudi, Histoires d’une mer au Sahara: utopies et politiques (Paris: Harmattan, 1997). -George R. Trumbull, “Body of Work: Water and the Reimagining of the Sahara in the Era of Decolonization,” in Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa, 87-112, edited by Diana K. Davis and Edmund Burke (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2011). Jackson Perry is a PhD candidate in the history department at Georgetown. He is currently completing his dissertation, titled "The Gospel of the Gum: Eucalyptus and the Modern Mediterranean, 1848-1896." Rob Christensen “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” –L. P. Hartley In my introduction to the undergraduate history major, we read John Lewis Gaddis’ The Landscape of History, wherein he discusses the fundamental problem of trying to put ourselves in the shoes of people we can never meet and whose thoughts we can only guess at. My recent research trip to Argentina highlighted for me a related problem that environmental historians must face: the difficulty of looking at a present environment that can be just as fundamentally different from the past as historical people were. The course of my research trip took me crisscrossing the pampas and northern Patagonia on double decker busses with big plate glass windows opening up a sweeping panorama of the areas I passed through. Although it was my first substantial experience outside Buenos Aires, I had read enough travelers’ accounts to recognize most of the names of the places we stopped – the colonial frontier guard of Luján, the outpost city of Carmen de Patagones, founded thousands of kilometers from the next settlement, and the seat of a powerful indigenous group at Trenque Lauquén. Despite the tacit knowledge that these places had grown into bustling modern cities I found myself somehow surprised by the parking lots and electronics shops. Even more than that, I was disappointed to not be able to experience the vastness of the Pampa that evoked sublime horror in European visitors (at least in the places I passed through). Instead of the unending sky and open plains I found lights in every direction, chic modernist houses, and the famous native grasses tall enough to hide a man on a horse replaced by alfalfa, soy, and corn (Fig. 1). The harried frontier soldiers who spent days or weeks on horseback carrying the messages that ended up in the archives I visited would scarcely recognize my experience of zipping from the capital to tierra adentro in a matter of hours in an air-conditioned bus. Most readers will recognize that this story is not unique in any way, but I think it is still illustrative. Coming to know the contemporary experience of the area you study is something of a rite of passage for historians that is implicitly meant to help us understand the experiences of people in the past, at least to an extent. Yet I doubt I would have ever been able to connect my experience of the contemporary pampa to the pampa I’ve read about in my 19th-century sources (Fig. 2); they feel categorically different and unrecognizable from each other. Replacing native grasses with crops would have been a change that the people I study understood, but fossil fuels have enabled changes in material and experienced environments that they could hardly have imagined. Climate change will only continue to exacerbate this disparity between past and present environments. My experience of coming to know today’s pampa after gaining a close knowledge of the historical one makes this contrast more palpable, as does my preindustrial time frame, which is a particular testament to the depth of the changes that industrialization and the Great Acceleration brought on all around the world. Historical inquiry is peculiar in that it generates knowledge that can only be understood through the lens of the present but which depends on a frame of reference that we can only approximate. It’s something all environmental historians have to consider as we try to strap on the sandals of the people we study (as Dr. Erick Langer, at Georgetown, likes to say). In some cases, these experiences might even be more of a hurdle than a steppingstone. My experience left me with another impression - don’t meet your heroes. Or perhaps instead, in environmental history, you can’t ever really experience the environments you study. I originally chose to study the Argentine frontier because I wanted to do my field work in a place like the one where I grew up, with wide open spaces and a reputation as a little wild. The irony is that although I was used to the profound ways that humans had impacted the natural landscapes around my hometown, it felt jarring when I went to another place that I also thought I knew well. Reading and writing historical narratives about past environments are to a certain extent incommensurable with the experiential knowledge we have of present environments, and that the people in our narratives had of theirs. But it’s the only shot we have. If I am disappointed to not be able to share the experiences of the people I study, doing environmental history is the only way to access those experiences at all today. Likewise, it’s the only way to appreciate the vastness of the changes that have occurred. Rob Christensen joined the PhD program in 2016. His dissertation looks at indigenous people, environmental change, and historical epidemiology centered around the late-nineteenth century Campaign of the Desert in Argentina. Before coming to Georgetown, he earned an MA at the University of New Mexico and tended a small farm. He is an avid fan of the Utah Jazz.

Bryna Cameron-Steinke For environmentally-minded historians, and particularly for those of us who study periods that suffer from a scarcity of written sources, archaeological data can be crucial. Excavations give insight into past material culture, providing information about past societies that is absent from the written record and offering tangible evidence of human interactions with the natural world. Yet, despite its many benefits, interpreting archaeological data isn’t easy, and shouldn’t be taken on lightly by those unfamiliar with the field. This summer, I had the opportunity to spend five weeks excavating at La Villa Romana Di Poggio Gramignano (VRPG), a Roman villa-turned Late Antique infant cemetery in Umbria, Italy. My experience taught me to appreciate, not only how difficult it is to properly use a pick-axe, but also the range of specializations within the field of archaeology and the rewards of interdisciplinary collaboration. VRPG is located about 6 km from Lugnano in Teverina in Umbria, on a steep hillside overlooking the Tiber river. It was first excavated by Daniela Monacchi of the Soprintendenza Archaeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio dell’Umbria, between 1982 and 1984, and again between 1987 and 1994 by David Soren, of the University of Arizona, in collaboration with the Soprintendenza Archaeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio dell’Umbria. While most of the site has not yet been uncovered, these initial excavations exposed large sections of the living quarters of the villa. Soren’s findings suggested that the villa was first built during the late-first century BCE. By the late first or early second century AD, the site’s hilltop setting destabilized the south side of the villa, causing it to collapse. While supports were constructed in the third century to prevent further damage, the use of the villa waned during the third century, and by the fifth century the villa had fallen into disrepair. The site was not fully abandoned until the sixth or seventh centuries, though, and the tens of infants uncovered at the site so far date to the mid-fifth century. Soren and his team uncovered no fewer than 47 burials at the site, ranging in age from prenatal to three years old (Soren 1999). The stratigraphy of the site, and paleoenvironmental data, suggested that the infants had been buried over a short timespan, leading Soren to blame a sudden epidemic of malaria, caused by Plasmodium falciparum (Soren 2003). While interdisciplinary analyses of the skeletal remains have corroborated this interpretation (Sallares and Gomzi 2000; Inwood 2017), the rooms that make up the cemetery were not fully excavated during Soren and Monacchi’s excavations. After two decades of inactivity, the site was reopened in 2016 under the leadership of David Soren and David Pickel, of Stanford University, in order to complete the excavation of the infant cemetery and gather additional information about the occupation of the site. I worked at VRPG between June 24th and July 26th 2019. While the five-week excavation certainly helped me develop my shovelling and pick-axe technique (as you can see in the picture above), it also gave me a behind-the-scenes view of archaeological research. The excavation at VRPG was a complex collaborative effort between a large group of researchers, including field archaeologists, ceramicists, zooarchaeologists, osteologists and conservators, all of whom worked together in order to excavate, catalog, and interpret the wide array of materials found on the excavation, from potsherds to human remains. During my time in Lugnano, I was able to gain some basic experience in these various sub-disciplines, and, by watching specialists at work, I learned to appreciate the great variety of skills necessary to carry out archaeological excavations. Our excavation also looked outside the traditional bounds of archaeology; in order to test Soren’s malaria hypothesis, we extracted teeth from some of the infants and sent them to the Ancient DNA Centre at McMaster University, where Hendrik Poinar and his team are mining them for remnants of pathogens and genetic material. While the results of these tests may not be available for some time, with any luck they will help to shed light on both the people who were buried at VRPG and the pathogens they harboured. After five weeks in Italy, I came home with a little bit of a tan, more than a few aches and pains, and a fresh perspective on the study of the past. Given my interest in ancient landscapes, I appreciated the opportunity to work directly with the natural environment of VRPG, to stand on the same hill and take in the same (or similar) view of the Tiber river as the site’s late Roman occupants centuries ago. Unlike most historians, archaeologists also work in close proximity to modern communities. Throughout the excavation, I was inspired by the level of interest our research received from the local community, who were not only supportive of our investigation into their local history, but also incredibly hospitable and patient to a bunch of foreigners, some of whom, myself included, could hardly string together a sentence of Italian. I have no doubt that this experience will help me to interpret archaeological data in my later research, and, when necessary, to reach out to those who know a lot more than me, whether they study bones, ceramics, or aDNA. While I don't think it’s necessary for every environmental historian to have personal experience on an archaeological site (though I would certainly encourage doing so), it is essential that we familiarize ourselves with archaeological methods and theories before attempting to make use of archaeological evidence. Better yet, environmental historians should aim to go even further, and include archaeologists in our academic circles and research projects. Generating and interpreting archaeological material isn’t easy—in fact, in my experience it’s a difficult, dirty, and dusty job. But it’s also the best way to sift through the sources available to us without misinterpreting them, leading to more interesting and productive scholarship. Bryna Cameron-Steinke is a PhD student of Environmental History at Georgetown University. Her research focuses on the development and use of marginal landscapes in early medieval northwestern Europe. She is interested in how climate and disease influenced the cultures and economies of marginal regions, namely marshlands and woodlands. References

J. Inwood, Identifying Malaria in Ancient Human Remains: A Molecular and Biochemical Approach. PhD diss., Yale University, 2017. R. Sallares and S. Gomzi, “Biomolecular archaeology of malaria,” Ancient Biomolecules 3 (2000): 195-213. D. Soren and N. Soren, A Roman Villa and A Late Roman Infant Cemetery: Excavations at Poggio Gramignano (Lugnano in Teverina) (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1999). D. Soren, “Can archaeologists excavate evidence of malaria?” World Archaeology 35.2 (2003): 193-209. |

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed