|

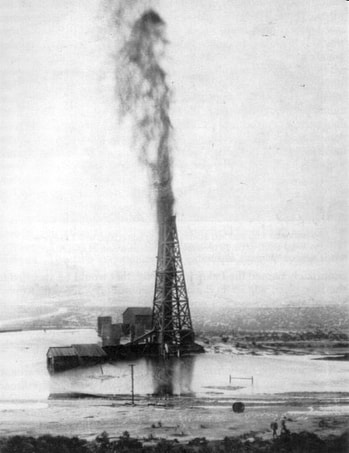

Matthew Johnson This post is part two of a field trip series where Matthew writes about his visits to raw materials extraction sites and how he understands them as an environmental historian. Read part one here. On March 15, 1910, the earth thundered underneath a crew of Union Oil geologists who were drilling for petroleum in a dusty patch of semi-arid desert and chaparral, a shrubland plant, on the southwestern edge of the San Joaquin Valley. The Lakeview No. 1 derrick rumbled and a huge column of oil and sand twenty-feet wide and two-hundred-feet tall shot into the air. The geologists had struck oil. For the next eight months, the Lakeview No. 1 gusher spewed oil uncontrolled, coating the surrounding countryside in petroleum and creating a huge lake of oil and sand at the derrick’s base that soon swallowed the derrick and drilling equipment. Workers eventually contained the lake using sandbags, but for ten more months oil continued to pour out of the well. Very little of the oil was saved and most evaporated or seeped into the ground. On September 10, 1911, the bottom of the crater caved in and the well ceased gushing oil. Workers have since filled in the crater and erected a plaque to mark the site. During the first half of the twentieth century, oil spills of such magnitude were not mourned as environmental disasters but celebrated as harbingers of oil wealth and material progress. The Lakeview gusher may have been short lived, but oil production in nearby oil fields was enduring. Lakeview No. 1 sits atop the Midway-Sunset oil field, the largest among a series of giant oil fields that were discovered in West Kern County between 1889 and 1911. The discovery of these oil fields set off a huge boom in commercial oil production that made California one of the most prolific oil producing states. In 1893, California was producing only 470,000 barrels of oil per year, but by 1910 the state was producing 73 million barrels of oil per year and its production accounted for more than one fifth of total oil production worldwide. During the following decade, California became the leading oil producer in the United States and Midway-Sunset alone was responsible for half of the state’s oil production. Oil companies erected thousands of wooden oil derricks across West Kern County and by 1923, California’s oil fields accounted for a full quarter of oil production worldwide. The Lakeview No. 1 gusher was one of the largest oil spills in the United States’ history. In eighteen months, 9.4 million barrels of oil gushed from the well, more than twice the 4.4 million barrels of oil that spilled into the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 and more than ten times the 900,000 barrels of oil spilled at Spindletop, a famous gusher in Texas, in 1901. The West Kern oil fields remain some of the most productive oil fields in the country. In 2016, California ranked third in oil producing states, behind Texas and North Dakota. Midway-Sunset is the largest oil field in California, producing 24.7 million barrels of oil in 2016. The top five oil fields in California are from West Kern County and in 2016 these five fields alone accounted for 52 percent of California’s oil production. California’s oil fields, along with other such fields across the world, revolutionized human history. Fossil fuel use facilitated unprecedented levels of population growth, urbanization, and motorization (among other things) that has reshaped how humans interact with each other and with the nonhuman world. The modern world as we know it would simply not function without petroleum. Although many recognize the essential role that petroleum plays in their lives, few have ever visited an oil field or refinery and fewer still pause to reflect on the fact that their consumption habits tie them to distant environments that produce and refine this black gold. The site of the Lakeview No. 1 gusher and the Midway-Sunset oil field are testaments to this distancing. Except for the plaque commemorating the well and the message board that recounts the site’s history, the dusty depression of the once-prolific gusher is otherwise indistinguishable from the surrounding desert. More noticeable from Highway 33 is the forest of oil pumps that stretches as far as the eye can see in some places. But I grew up in California and know few other Californians who have ever driven down highway 33 and fewer still who would recognize the name Midway-Sunset or the historical importance of the West Kern oil fields. In 2014, my family and I visited the oil fields. As I stared out the window at the industrial landscape of steel pipelines and oil pumps unfolding across the desert in front of me I struggled to reconcile how this foreign and forbidding landscape was at the heart of a standard of living I have come to take for granted. After visiting the site of the Lakeview No. 1 gusher and stopping to take photos of the Midway-Sunset oil field, we concluded our trip at the Western Kern County Oil Museum in Taft. The local chapter of the American Association of University Women established this amazing museum in 1974 when it rallied to save the last of Kern County’s wooden derricks. The site has a wealth of information about the history of the oil industry, both local and worldwide. During my childhood and adolescence, I had traveled through the San Joaquin Valley many times to visit relatives in Southern California. As our family sped down highway 5, I used to fight boredom as I stared out the window at the endless grape and almond fields. Studying environmental history has changed my comprehension of these places. As a child, I never would have imagined that just beyond the agricultural horizon (which has its own rich history) there were sites of such intrigue and importance to the energy regime of the modern world. Studying environmental history has transformed a landscape of boredom into one of endless fascination. Understanding the environmental history of a place helps make visible distant landscapes and people that are essential to maintaining a unique and unprecedented standard of living that many have come to accept as normal. Every day, thousands of people speed along Highway 5 to and from urban and suburban centers, in cars that burn oil, without a second thought to the oil fields thirty miles west that sustain their trip and the cities and suburbs they call home. The Midway-Sunset oil field, and the other coal and oil fields like it across the world, are at the very heart of modern life and it is surprising that so many people overlook them. Visiting sites of energy extraction and production while also learning about their history is an important step in reconciling the deep ambiguities and unease that characterize our relationship with fossil fuels and their impact on the nonhuman world. For more information about Californian oil history see: Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Touchstone, 1991); Paul Sabin, Crude Politics: The California Oil Market, 1900-1940 (University of California Press, 2004); and the websites for the West Kern Oil Museum, San Joaquin Valley Geology, and California Department of Conservation. Matthew Johnson is a PhD Student at Georgetown University who studies modern Latin American and Caribbean environmental history. His dissertation will look at the social and environmental costs of large hydroelectric dams built by Brazil’s military government in the 1970s and 1980s.

0 Comments

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed