|

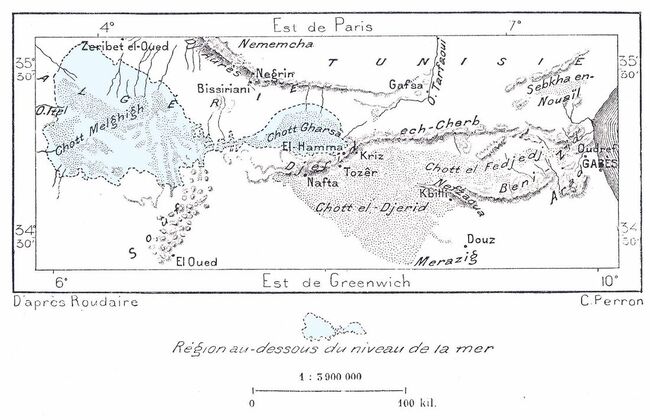

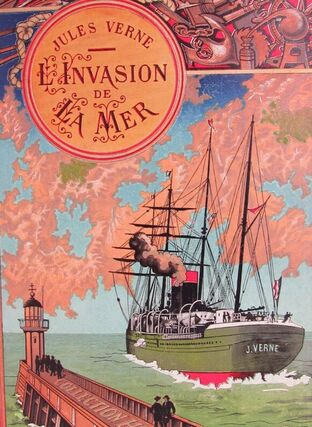

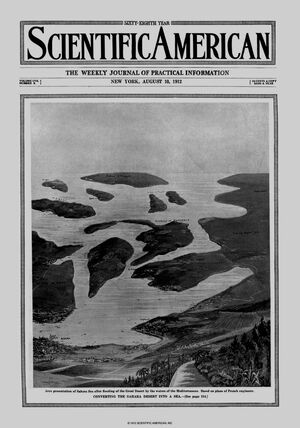

Jackson R. Perry Captain François Roudaire (1836-1885) was convinced that a large inland sea could be created in the Sahara Desert across southeastern Algeria and southern Tunisia. The French military surveyor received funding from public and private sources in the 1870s to carry out feasibility studies on that region’s chotts or shebkas, seasonal salt lakes that are sometimes found below sea level. The centerpiece of his proposal was a long canal from Tunisia’s coast on the Gulf of Gabes to low-lying chotts in the interior. Once the Mediterranean began to flow into the desert, Roudaire believed, the Saharan climate would become cooler and the rate of precipitation in the region would increase. His announcement in the widely-read Parisian periodical Revue des deux Mondes on May 15, 1874 that French engineers could build “une mer intérieure en Algérie” stirred up the imaginations of the capital’s political, social, and scientific elite. Ferdinand de Lesseps, whose success in the Suez Canal project led him to seek similarly grandiose opportunities to remake the world (e.g. in Panama), soon joined the project and helped with funding. Roudaire’s most prominent critic was Ernest Cosson, a senior member of the Société botanique de France and an expert on North African botany. Cosson and many of his colleagues in metropolitan scientific associations rejected the plan for several reasons: its clearly negative consequences of an infusion of salt water for native flora (particularly the date trees on which Saharan oasis agriculture depended); the engineering nightmare posed by a canal up to 150 miles in length; the highly questionable nature of Roudaire’s claims about climatic change; and the social unrest that would have followed the substantial expropriation of native land. The scientific community’s dismissal of the scheme, the state’s loss of interest when the difficulty of the project became clear, and the deaths of Roudaire in 1885 and de Lesseps in 1894 ended the Saharan Sea project. However, the Saharan Sea dream has lived on. In fiction, it first appeared in British journalist Louis Tracy’s futuristic An American Emperor: The Story of the Fourth Empire of France (serialized in Pearson’s Weekly, 1896-97), which features an immensely wealthy American businessman who arrives in Paris intent on making the inland sea a reality. Jules Verne’s L’Invasion de la mer (1905) describes a future conflict between colonizers attempting to build the sea and native Saharans who opposed the European effort. In Verne’s story, an earthquake that occurs at the climax of the tale causes the Mediterranean to engulf the chotts of the Sahara ahead of schedule. Several historians have already ably examined the scheme as it relates to the history of European imperialism in Africa and the history of European understandings of desertification and geo-engineering (See suggestions for further reading below). What I find illuminating in the Roudaire affair is the important role of newspapers and journals. The power of popular media to drive scientific inquiry has become quite clear in my dissertation on another ecological modification scheme of the late 19th century: the dissemination of the Australian eucalyptus tree to malarial environments in the Mediterranean, South Africa, India, and elsewhere. “The Age of Steam and Print,” as James Gelvin and Nile Green have dubbed the late 19th century, was a golden age of media frenzies and of international searches for the filler material that we sometimes call clickbait today. The newly cheap cost of printing in the 19th century, the revolutions in transportation and communication technology that enabled interesting stories to spread across national borders and oceans, and the competitive business environment of journalism, created strong incentives for editors and writers to prioritize quantity over quality, and to put fascination ahead of verification. The fantasy that Roudaire started in the Revue des deux Mondes, a popular avenue around the gatekeepers who controlled the publications of the traditional scientific societies, spread quickly throughout the European and American presses. Editors happily built the canals for Roudaire’s Saharan Sea dream to invade their empty column inches. “As it is today,” Hocine Bendjoudi and René Létolle wrote about the Roudaire episode, "journalists lacking copy periodically revived the affair in the opinion press." The dream of creating a Saharan Sea still has clickbait value today. Numerous videos on Youtube, and articles in Conde Nast Traveler, Big Think, and Gizmodo under its ’Secret History’ tag, rehash previous work on the Roudaire scheme and its intellectual successors. The basis of European conceptions of the central Sahara changed from ignorance to fascination in the era of Roudaire, Philip Lehmann argues, and there it remains today. In our modern media environment, ridiculous schemes have lives of their own, periodically entertaining audiences for years and entrenching warped understandings of the desert as a vacant land awaiting improvement. Citations and recommendations for further reading: -Diana K. Davis, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016). -Michael Heffernan, “Bringing the Desert to Bloom: French Ambitions in the Sahara Desert During the Late Nineteenth Century - The Strange Case of ‘la mer intérieure,’” in Water, Engineering, and Landscape: Water Control and Landscape Transformation in the Modern Period, 94-114, edited by Denis E. Cosgrove and Geoffrey E. Petts (London: Belhaven Press, 1990). -Meredith McKittrick, "An Empire of Rivers: The Scheme to Flood the Kalahari, 1919–1945", Journal of Southern African Studies 41, n. 3 (2015): 485-504. -Philipp Lehmann, “Changing Climates: Deserts, Desiccation, and the Rise of Climate Engineering 1870-1950,” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2014). -René Létolle and Hocine Bendjoudi, Histoires d’une mer au Sahara: utopies et politiques (Paris: Harmattan, 1997). -George R. Trumbull, “Body of Work: Water and the Reimagining of the Sahara in the Era of Decolonization,” in Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa, 87-112, edited by Diana K. Davis and Edmund Burke (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2011). Jackson Perry is a PhD candidate in the history department at Georgetown. He is currently completing his dissertation, titled "The Gospel of the Gum: Eucalyptus and the Modern Mediterranean, 1848-1896."

0 Comments

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed