|

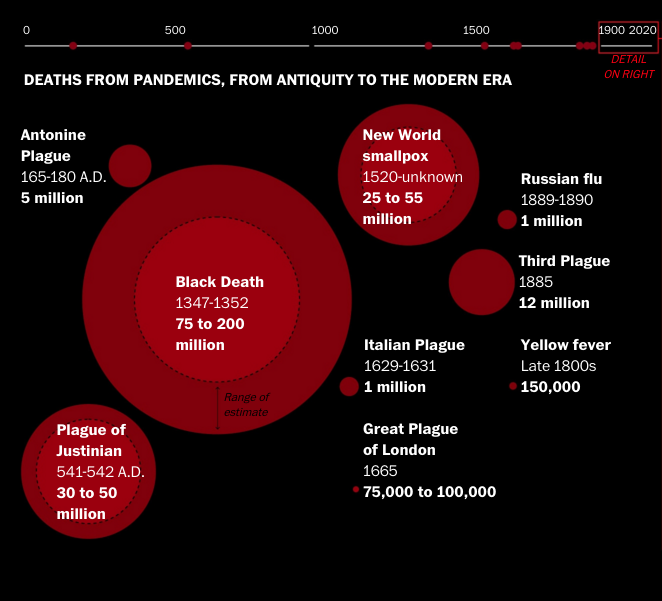

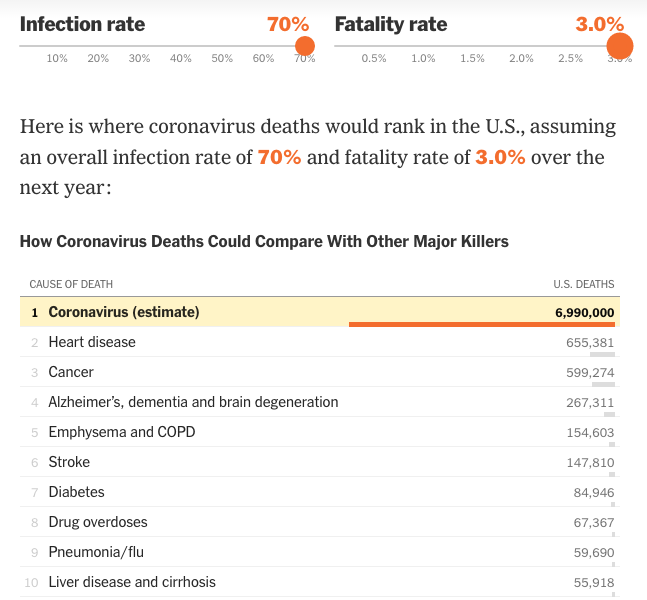

Tim Newfield Another day, another spillover. Is history repeating itself? Sure, in some respects, but no, not really. Novel human diseases may emerge every year, but not like this. SARS-CoV-2 has pulled off what countless other pathogens have failed to: it’s globalized and become endemic. Sequence data indicates that the spillover happened in late November (1). Since then well over four million confirmed cases and 290,000 deaths have been reported in more than 215 countries and territories. Worse yet, it is next to certain that millions of more COVID-19 cases (severe, moderate, mild and asymptomatic) have gone unconfirmed and that official tallies omit tens of thousands of lives lost to COVID-19. A large percentage of the world’s population has been in “lockdown” for weeks. The first wave is ongoing in some regions; in others the second has begun. Months into the pandemic, it’s starting to sink in that this disease isn’t going anywhere soon if at all. This is a crisis unlike any other. That’s not to say it’s worse than any other novel disease emergence. It’s not. SARS-CoV-2 has nothing on the great influenza (1917-20) or the Black Death (1346-52), let alone smallpox or measles, which spilled over once too. A number of other old diseases (like malaria and tuberculosis to name but two) likewise make the current outbreak seem insignificant, but of course it’s not. The numbers make that clear. It has been, and will continue to be for some time, a public health crisis and a source of considerable tragedy. It’s not insignificant, it’s just different. That hasn’t always been clear in COVID-19 coverage, however, and not drawing attention to everything that separates our current pandemic from those of the past may have come at a cost.  Tionfo della morte, Pisa, fresco, mid-fourteenth century. Bodies of secular and religious elites, women and men, heaped in a mass grave. Death harvests above. Long thought painted shortly after the Black Death by Agnolo Gaddi or Francesco Traini, more recently attributed to the obscure Buonamico Buffalmacco and dated to c.1335-40. The Black Death and the current coronavirus pandemic are worlds apart. Courtesy of the author. Epidemiologists say “if you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic”. Historians and journalists would do well to adopt the same mantra. No two diseases nor any two moments in time are the same. Different as it may be, SARS-CoV-2 is going to leave a perceptible mark on history, like other pandemics have. There is talk already of life before and life after this pandemic. Things will change, we’re told. Whether they change for the better or not, a myriad of impacts, big and small, stemming from the outbreak and the lockdown will be visible years down the line when historians look back. But what should historians do now? Can the stewards of the past contribute in meaningful ways as the disease continues to spread? These are tricky questions. It’s not the business of history, after all, to curb disease outbreaks or to forecast what lies ahead. Serial intervals, infection rates, and reproduction numbers are not the bread and butter of history. Predicting what would or will happen has proved tough for even the most experienced of epidemiologists. So, historians should probably do something else. Lessons from the past, it has been said (2), normally come from outside the discipline of history, but there’s been no shortage recently of historians willing to draw linkages between the present and what’s come before. Journalists have had a field day with history too. If pseudo-epidemiology has grown exponentially in recent months, the number of practicing armchair historians at present has broken with all precedent. Historians, of course, could put things in context. They could help us understand how it is that we ended up here, an essential step in making sure we don’t stay here. There’s no shortage of topics. In some respects, it all matters, from globalization and urbanization, to public health preparedness and the rise and reach of health internationals, to climate change and our exploitation of animals and ecosystems. These big subjects are just a start. Historians should also be in the business of drawing a hard line between present and past pandemics. I’ve found many of the history lessons, by and largely given by journalists, in the context of the current pandemic hard to stomach. Most are underdeveloped. This isn’t surprising, as newspapers and blogs have word limits (I’ve already spent a third my allowance), but the simplification those mediums require can deteriorate quickly. Before you know it, something’s been oversimplified, anachronism’s been committed, and both the present and the past have been misrepresented. The lessons are also hard to stomach because they imply or assume that our diseased present and some diseased past are commensurate. They suggest that what we’re living through has been lived through before. That is, that we haven’t paid enough attention to the past or recognized our mistakes. To some extent, this is, of course, the case. Pandemics aren’t new and spillovers are common. Sadly, xenophobia, racism and disease also have a long history. Lockdowns, quarantines, social distancing, they’re all old news too. There’s no novelty in the mad race for a vaccine either and powers that be have been seizing upon epidemics to push their agendas for centuries. The fatness of one’s wallet has as well always mattered in the face of a disease outbreak and I doubt there have been many epidemics that haven’t intensified socio-cultural anxieties, racial and geographical privileges, and economic disparities. Ok, but while there is no shortage of parallels to uncover, it’s certainly true that we have to ignore a lot to find them. If the oversimplifying weren’t bad enough, the straightforward lessons (and warnings) don’t seem to be working. This isn’t the first time historians, armchair or not, have jogged our memory about these things, after all. During (and after) the 2013-15 Ebola epidemic, the 2009 influenza pandemic, or the 2003 SARS outbreak, for instance, we heard much the same (though perhaps less often). As valuable as these unheeded lessons might be (or could be if we actually acted on them), that they almost always come from some great historical plague is, to my mind, a real problem. Drawing lines between the great influenza or the Black Death and SARS-CoV-2 implies that our current crisis is on par with the largest, most significant disease outbreaks of history. As early as January 25th (3), the U.S. paper-of-record, the New York Times, was drawing linkages between the current pandemic and that which was wrapping up about this time a century ago, the great influenza. They did so again on 1 February (4). At that time, fewer than 15,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 300 deaths had been reported. By March 1st, the NYT had linked COVID-19 with the great influenza in no fewer than 17 articles (5). On February 27th, the same paper began drawing the same linkage on their podcast The Daily. That day, their guest, the NYT’s own resident ‘plagues and pestilences’ journalist, expressed concern about being “too alarmist”, but he didn’t hesitate to claim “this one”, that is the COVID-19 outbreak, “reminds me of what I have read about the 1918 Spanish influenza” (6). Associations in COVID-19 coverage, usually quick and flippant, with truly great plagues, like the century-old influenza pandemic, accumulated in no time. By mid-March the Black Death started gaining traction. The most infamous later outbreaks of the second plague pandemic, the 1665-66 plague of London and 1720-22 Provençal Peste (or plague of Marseille), also eventually got their due. I knew journalists were digging deep when I started encountering references to the more obscure Antonine and Justinianic plagues of the second and sixth centuries. Less surprising, Thucydides’ better-known Athenian plague also went viral. I’d be contradicting myself if I said these connections were absurd – as noted, historians aren’t in the business of predicting the future and SARS-CoV-2 isn’t over – but these connections were as absurd then as they are now. It’s been clear for months that COVID-19 is not going to rank among the greatest pandemics of history. This may be hard to hear, or seem improbable, considering the scale and duration of the global lockdown and that millions have been infected and hundreds of thousands killed, but it’s not on par with the great influenza let alone the great plagues of premodernity. There are countless reasons for this. We might start with the fact that it’s hard to be a premodern plague in 2020. But even if we were living in 165, 541 or 1346, the current pandemic wouldn’t be one of the great plagues. In fact, had SARS-CoV-19 spilled over then, it wouldn’t have made history.  Infographic from M. Rosenwald, “History’s deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America” Washington Post 7 April 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/local/retropolis/coronavirus-deadliest-pandemics/ There are too many issues with this figure to discuss here. A few: even rough mortality estimates for the Antonine and Justinianic plagues are suspect. Some question whether the Antonine plague was a singular disease outbreak, let alone one of pandemic scale. That 50 million might have died in the Justinianic plague is an absurd claim considering the evidence at hand. At the same time, some historians have argued the ‘Italian plague’ of 1629-31 killed twice the number listed here. That the Black Death claimed upwards of 200 million lives is hard to make sense of. Although the Black Death has suffered for more than a century from extreme Eurocentrism, recent scholarship has emphasized that the great mid-fourteenth-century pandemic spread widely and killed millions in southwest Asia and North Africa, and that it possibly disseminated across large areas of Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa too. Perhaps the total mortality surpassed 100 million, but that is as far from certain as you can get, particularly if the pandemic is fixed the standard European dates of 1347-52. (7) Using the past to sensationalize the present helps attract and maintain readers, I have no doubt. Disease history sells, even when we aren’t living through a pandemic. But could connecting the present outbreak to the biggest plagues on record come at a cost? No matter how casual or careless the connection, one might think repeatedly putting SARS-CoV-2 side-by-side with the great influenza or the Black Death has the capacity to do harm. Misusing history in this way might affect the mental health of millions of readers. I’d say this is all the more likely if most readers know great historical plagues only vaguely as major, world-changing events, that is, if they aren’t ready with all the stats they need to understand how ludicrous the connections are. Ties to the great plagues of old, whether they’re meant to teach something or not, could unnecessarily cause or aggravate anxiety and fear. They could help whip up panic. I’d like to think these linkages to past plagues were (and are still) intended to encourage social distancing – as in bad history done purposefully to frighten people to do what’s right: stay inside, break chains of transmission and protect the most vulnerable. But I’m not so sure. Fear sells and considering how many reports there have been playing up this novel coronavirus’ “mysterious origins”, “freak mutations” (8), and seemingly shifting symptomatology, I don’t think history has been deliberately played with for the sake of the greater good. If fear didn’t sell, worse case scenarios (9), and all the unknown variables imaginable wouldn’t steal the bulk of the headlines. To give but a single example: Well after the NYT cemented their connection between COVID-19 and the great influenza, they published an online article in mid-March with a ‘range slider bar’ that allowed readers to play with population infection and case fatality rates and to forecast by themselves what was to come. This was thoughtless pseudo-epidemiology at best. If one maxed out the infection rate bar at 70 percent and the fatality rate bar at three percent, as anyone would, they learned nearly seven million Americans were going to die (10). This is but one example. There are many, many more. That we were told early on in the NYT to “go medieval” (11) on the “Wuhan” or “Chinese” virus (12), might have tipped us off that the past was going to be used carelessly in the media and that important earlier lessons, about xenophobia, racism and fixing geographic labels to pathogens for instance, were going to be ignored in COVID-19 coverage. Historians have been helping to set things straight (13), but ideally they would fact check the fact checkers, as it were, in the very same outlets and reach the same large, nonacademic audience. But bringing the crisis down to size risks discouraging people from doing what they need to do. It could be counterproductive to point out that no fewer than 675,000 Americans died in the three waves of influenza that passed through the country in 1918-19, and that that’s about 2.3 million deaths if we multiply to reflect today’s population size, or that no historian thinks fewer than ten million people died in India during that century-old pandemic – the equivalent of well more than 45 million deaths now. That the Black Death claimed tens of millions of lives in the wider Mediterranean region and Europe, perhaps 45 percent of the total affected population, in just a few years, halved the populations of countless cities in mere months, and spread and killed far more widely yet, makes our current crisis look even smaller. Bringing the crisis down to size isn’t going to persuade people to do what they should. Historians have much to do, but they walk a fine line if they undercut misleading linkages with past plagues – that undercutting risks disrespecting the gravity of the crisis for those affected and those most at risk. It could also hurt our best efforts to mitigate the pandemic. References (1) K. Anderson et al, “The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2” Nature Medicine 26 (2020), pp. 450-452. (2) R. Peckham, “COVID-19 and the anti-lessons of history” The Lancet 395 (2020), pp. P850-852, but do read A. White, “Historical linkages: epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia” The Lancet 395 (2020), pp. P1250-1251, C. Ermus, “The danger of prioritizing politics and economics during the coronavirus outbreak” Washington Post 13 March 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/13/danger-prioritizing-politics-economics-during-coronavirus-outbreak/ (3) D. Grady, “Chicago woman is second case to be confirmed in the U.S., the C.D.C. says” NYT 25 January 2020, A8. There were 1,320 confirmed cases at the time. Perhaps it should be said that the NYT is one of only three papers I read regularly. I have yet to review my notes on the other two. (4) D. Grady, C. Rabin, “C.D.C. imposes 2-week quarantine on evacuees from Wuhan” NYT 1 February 2020, A11. (5) D. Grady, “Chicago woman is second case to be confirmed in the U.S., the C.D.C. says” NYT 25 January 2020, A8; D. Grady, C. Rabin, “C.D.C. imposes 2-week quarantine on evacuees from Wuhan” NYT 1 February 2020, A11; D. McNeil Jr., “Rise in cases suggests epidemic is pandemic” NYT 3 February 2020, A12; R. Rabin, “A deadly new contagion” NYT 4 February 2020, D1; A. Qin et al, “Beijing imposes extreme limits on ill in Wuhan” NYT 7 February 2020, A1; R. Gladstone, “As Chinese grapple with a new illness, an old stigma is revived” NYT 11 February 2020, A11; R. Rabin, “Warehousing patients also has its hazards” NYT 12 February 2020, A8; M. Richtel, “Getting online keeps lives on track for those in quarantine” NYT 19 February 2020, A8; R. Rabin, “Scientists study why the illness seems to be hitting men harder than women” NYT 21 February 2020, A7; F. Stockman, L. Keene, “In California, the quest for a new quarantine site sets off a rare legal battle” NYT 25 February 2020, A9; M. Osterholm and M. Olshaker, “How to mitigate the impact of the coronavirus” NYT 25 February 2020, A27; J. Goldstein and J. Mckinley, “Stockpiling supplies and working through outbreak scenarios” NYT 28 February 2020, A23; P. Krugman, “Pandemic, meet the Trump personality cult” NYT 28 February 2020, A25; D. McNeil Jr, “Censorship is never the best medicine in an epidemic” NYT 29 February 2020, A15; D. Phillipps, “U.S. military prepares plans to battle an invisible enemy” NYT 1 March 2020, A27; D. McNeill Jr., “To take on the coronavirus, go medieval on it” NYT 1 March 2020, SR3; N. Kristof, “Is this ‘the big one’?” NYT 1 March 2020, SR11. (6) “The coronavirus goes global” The Daily 27 February 2020, 03:06-04:46. Everyone should know by now that there wasn’t much particularly ‘Spanish’ about the 1917-20 influenza pandemic other than that in the West it was reported early on in Spain, a neutral country in WWI and without wartime censorship. (7) L. Mordechai et al, “The Justinianic plague: an inconsequential pandemic?” PNAS 116 (2019), pp. 25546-25554; N. Varık, Plague and empire in the early modern Mediterranean world: the Ottoman experience, 1347-1600 (CUP, 2015); M. Green, “Putting Africa on the Black Death map: narratives from genetics and history” Afriques 9 (2018), doi.org/10.4000/afriques.2125; T. Brook, Great state: China and the world (Profile Books Ltd, 2019); H. Barker, “Laying the corpses to rest: grain embargoes and the early transmission of the Black Death in the Black Sea, 1346-1347” Speculum, forthcoming. (8) D. McNeil Jr, “Rise in cases suggests epidemic is pandemic” NYT 3 February 2020, A12; idem, “What the next year (or two) may look like” NYT 19 April 2020, A1. J. Corum and C. Zimmer, “How coronavirus mutates and spreads” NYT 30 April 2020 should be read alongside N. Grubaugh et al, “We shouldn’t worry when a virus mutates during disease outbreaks” Nature Microbiology 5 (2020), pp. 529-530. The inclusion of the remarks of Dr. S. Bell in C. Zimmer, “On the trail of New York’s Covid-19 cases” NYT 14 April 2020, D7, is to be noted. (9) C. Zimmer, “2 scenarios for Covid-19: best and worst” NYT 22 March 2020, SR2. (10) J. Katz, “Could coronavirus cause as many deaths as cancer in the U.S.? Putting estimates in context” NYT 16 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/16/upshot/coronavirus-best-worst-death-toll-scenario.html) (11) D. McNeill Jr., “To take on the coronavirus, go medieval on it” NYT 1 March 2020, SR3. (12) In late January and early February, the NYT referred to “Wuhan virus”, “Wuhan coronavirus”, “Wuhan strain,”, “Chinese virus”, “China virus” in no fewer than 17 articles: R. Rabin, “First patient with the mysterious illness is identified in the U.S.” NYT 22 January 2020, A10; D. Grady, “As new virus spreads from China, specialists see grim reminders” NYT 23 January 2020, A8; A. Qin and V. Wang, “China closes off city at center of virus outbreak” NYT 23 January 2020, A1; Y. Huang, “Is China setting itself up for another epidemic?” NYT 23 January 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/opinion/coronavirus-china-wuhan.html; M. Baker, “Texas student is monitored after a trip” NYT 24 January 2020, A7; D. Grady, “Chicago woman is second case to be confirmed in the U.S., the C.D.C. says” NYT 25 January 2020, A8; M. Baker and J. Singer, “Chinese-Americans feel glare and rush to help” NYT 25 January 2020, A8; J. Gorman, “They are mammals, they fly and they host pathogens” NYT 29 January 2020, A7; R. Rabin, “Beijing says expert teams are welcome” NYT 29 January 2020, A7; D. Grady, “Outside China, racing to halt virus’s spread” NYT 30 January 2020, A1; A. Stevenson, “Borders sealed and flights banned as world works to contain virus” NYT 2 February 2020, A11; D. McNeil Jr., “Rise in cases suggests epidemic is pandemic” NYT 3 February 2020, A12; R. Rabin, “A deadly new contagion” NYT 4 February 2020, D1; R. Rabin, “Experts fear patients spreading virus even without signs of symptoms” NYT 5 February 2020, A9; C. Krauss, “Virus threatens an oil industry that’s already ailing” NYT 5 February 2020, B1; A. Harmon, “Inside the race to contain America’s first confirmed case” NYT 6 February 2020, A6; C. Buckley, “Whistle-blower on China virus succumbs to it” NYT 7 February 2020, A1. But also see: M. Rich, “Virus fuels anti-Chinese sentiment overseas” NYT 31 January 2020, A1, and notably, L. Yi-Zheng, “The coronavirus and ‘jinbu’ foods” NYT 23 February 2020, SR2. For an earlier “China virus” in the NYT: A. Jacobs, “China virus kills 22 and sickens thousands” NYT 3 May 2008, A6. (13) A few examples: J. Crawshaw, “Quarantine – an early modern approach” History & Policy 12 March 2020, http://www.historyandpolicy.org/opinion-articles/articles/quarantine-an-early-modern-approach; M. Bresalier, “Covid-19 and the 1918 ‘Spanish flu’: differences give us a measure of hope” History & Policy 2 April 2020; M. Zuk and S. Jones, “Covid-19 is not your great-grandfather’s flu – comparisons with 1918 are overblown” Greenly Tribune 23 April 2020 https://www.greeleytribune.com/opinion/marlene-zuk-and-susan-d-jones-covid-19-is-not-your-great-grandfathers-flu-comparisons-with-1918-are-overblown/; G. Geltner, “Getting medieval on Covid? The risks of periodizing public health” History News Network 29 March 2020, http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/174758; N. Varlık with C. Horn, “Covid-10 impact: the history of plague and contagion” University of South Carolina, https://www.sc.edu/uofsc/posts/2020/03/covid_impact_nukhet_varlik.php#.Xrne9yMrJjc; T. Brook, “Blame China? Outbreak orientalis, from the plague to coronavirus” The Globe and Mail 13 February 2020, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-outbreak-orientalism-from-the-plague-to-coronavirus-why-is-the-west/; A. Heinrich, “Before coronavirus, China was falsely blamed for spreading smallpox. Racism played a role then, too” The Conversation 6 May 2020, https://theconversation.com/before-coronavirus-china-was-falsely-blamed-for-spreading-smallpox-racism-played-a-role-then-too-137884. Cf. G. Kolata, “Coronavirus is very different from the Spanish flu of 1918. Here’s how” NYT 9 March 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/health/coronavirus-is-very-different-from-the-spanish-flu-of-1918-heres-how.html/ Dr. Tim Newfield is an Assistant Professor in History and Biology at Georgetown. He is an environmental historian and historical epidemiologist, and he regularly leads seminars on global infectious disease history.

1 Comment

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed