|

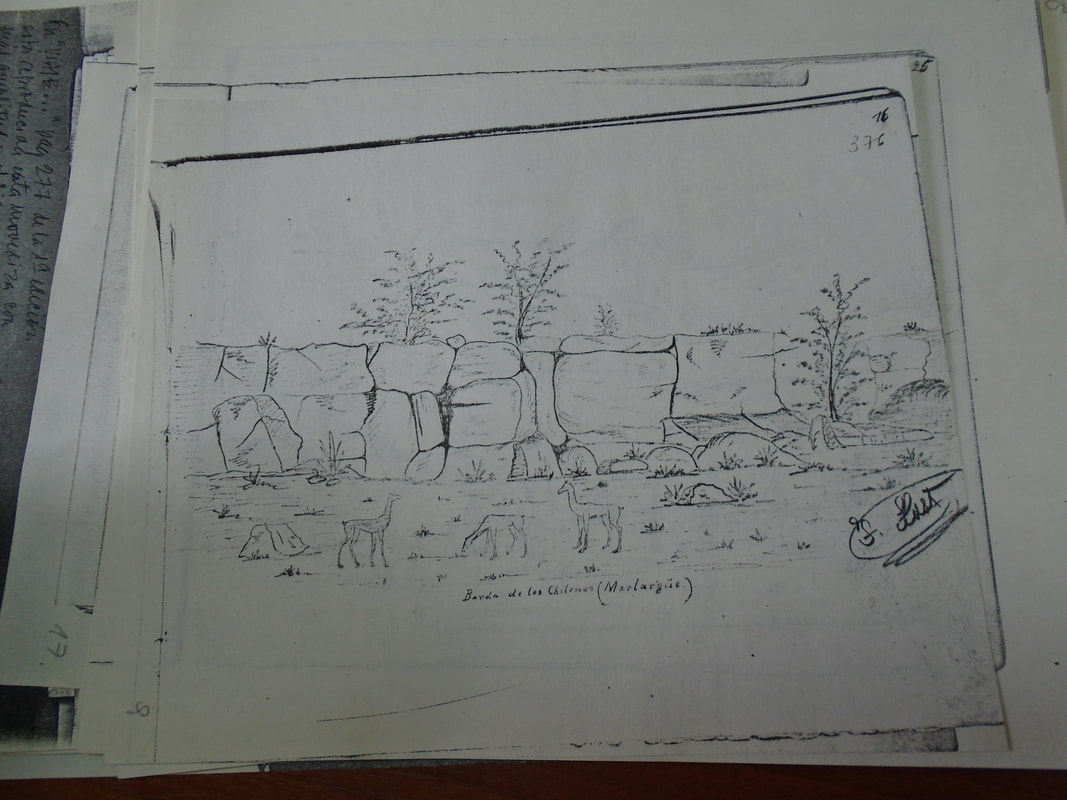

Rob Christensen “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” –L. P. Hartley In my introduction to the undergraduate history major, we read John Lewis Gaddis’ The Landscape of History, wherein he discusses the fundamental problem of trying to put ourselves in the shoes of people we can never meet and whose thoughts we can only guess at. My recent research trip to Argentina highlighted for me a related problem that environmental historians must face: the difficulty of looking at a present environment that can be just as fundamentally different from the past as historical people were. The course of my research trip took me crisscrossing the pampas and northern Patagonia on double decker busses with big plate glass windows opening up a sweeping panorama of the areas I passed through. Although it was my first substantial experience outside Buenos Aires, I had read enough travelers’ accounts to recognize most of the names of the places we stopped – the colonial frontier guard of Luján, the outpost city of Carmen de Patagones, founded thousands of kilometers from the next settlement, and the seat of a powerful indigenous group at Trenque Lauquén. Despite the tacit knowledge that these places had grown into bustling modern cities I found myself somehow surprised by the parking lots and electronics shops. Even more than that, I was disappointed to not be able to experience the vastness of the Pampa that evoked sublime horror in European visitors (at least in the places I passed through). Instead of the unending sky and open plains I found lights in every direction, chic modernist houses, and the famous native grasses tall enough to hide a man on a horse replaced by alfalfa, soy, and corn (Fig. 1). The harried frontier soldiers who spent days or weeks on horseback carrying the messages that ended up in the archives I visited would scarcely recognize my experience of zipping from the capital to tierra adentro in a matter of hours in an air-conditioned bus. Most readers will recognize that this story is not unique in any way, but I think it is still illustrative. Coming to know the contemporary experience of the area you study is something of a rite of passage for historians that is implicitly meant to help us understand the experiences of people in the past, at least to an extent. Yet I doubt I would have ever been able to connect my experience of the contemporary pampa to the pampa I’ve read about in my 19th-century sources (Fig. 2); they feel categorically different and unrecognizable from each other. Replacing native grasses with crops would have been a change that the people I study understood, but fossil fuels have enabled changes in material and experienced environments that they could hardly have imagined. Climate change will only continue to exacerbate this disparity between past and present environments. My experience of coming to know today’s pampa after gaining a close knowledge of the historical one makes this contrast more palpable, as does my preindustrial time frame, which is a particular testament to the depth of the changes that industrialization and the Great Acceleration brought on all around the world. Historical inquiry is peculiar in that it generates knowledge that can only be understood through the lens of the present but which depends on a frame of reference that we can only approximate. It’s something all environmental historians have to consider as we try to strap on the sandals of the people we study (as Dr. Erick Langer, at Georgetown, likes to say). In some cases, these experiences might even be more of a hurdle than a steppingstone. My experience left me with another impression - don’t meet your heroes. Or perhaps instead, in environmental history, you can’t ever really experience the environments you study. I originally chose to study the Argentine frontier because I wanted to do my field work in a place like the one where I grew up, with wide open spaces and a reputation as a little wild. The irony is that although I was used to the profound ways that humans had impacted the natural landscapes around my hometown, it felt jarring when I went to another place that I also thought I knew well. Reading and writing historical narratives about past environments are to a certain extent incommensurable with the experiential knowledge we have of present environments, and that the people in our narratives had of theirs. But it’s the only shot we have. If I am disappointed to not be able to share the experiences of the people I study, doing environmental history is the only way to access those experiences at all today. Likewise, it’s the only way to appreciate the vastness of the changes that have occurred. Rob Christensen joined the PhD program in 2016. His dissertation looks at indigenous people, environmental change, and historical epidemiology centered around the late-nineteenth century Campaign of the Desert in Argentina. Before coming to Georgetown, he earned an MA at the University of New Mexico and tended a small farm. He is an avid fan of the Utah Jazz.

0 Comments

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed