|

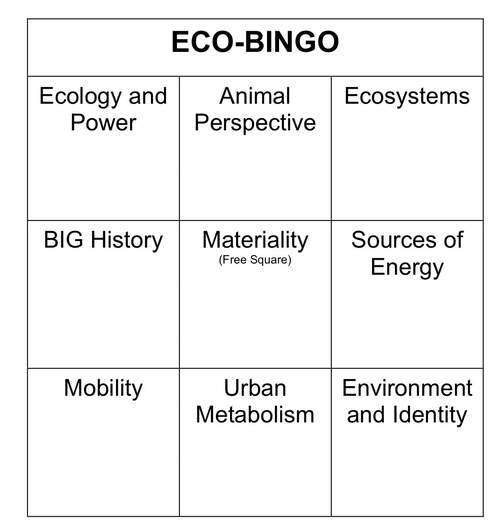

Rebecca Andrews “B seven. G twenty-four. O eighteen.” As the announcer neatly ticks off the options that could let you take home that BINGO prize, the apparently random assortment of numbers in front of you begin to take on shape. Patterns emerge and your excitement increases with every square that connects. But, as any seasoned BINGO player will tell you, listening for the next one is as important as marking down the ones previously read. If you fall behind because you over-celebrated getting the second to last block, you may miss the announcement of your winning square. Finding what the pattern looks like, seeing the gaps of what you need next, and paying attention are, in my view, the fundamentals of BINGO. As it happens, these could also be considered the fundamentals of my experience this past semester in Professor McNeill’s Environmental History Seminar. Professor McNeill began the seminar asking all five students to nominate themes for discussion throughout the semester. The topics suggested ranged widely, from “Big History” and “Energy” to “Urban Metabolism,” showing the varied interests and priorities of the room. As a newcomer to environmental history, the full blackboard and resulting skeleton syllabus was my first exposure to a summary of which historical themes might mesh well with environmental thinking. As it turned out, that appeared to be pretty much anything – a random assortment of topics to an inexperienced eye. As the semester proceeded, patterns emerged. Historical and environmental questions blended together and grew from class to class. What does it mean to write accessibly? What about scientifically? What do we, as both historians and readers, gain from including and exploring the materiality of our subject matter? Some were more detailed (what is copper, bison, or soil, anyway?) and some were much bigger (should every history start with the Big Bang?). With each new idea, every class encouraged a reassessment of your own work with a fresh environmental perspective or a new method. The weekly exercise of identifying “grist for your mill” encouraged us to layer concepts on individual projects, paying attention to what’s out there and assessing how it had been applied. Reading, listening, thinking, and debating the way through each book created more informed views of what gaps existed. If in reading the last three paragraphs you did not immediately think to yourself, “Now this looks a lot like the fundamentals of BINGO,” don’t worry. Maybe the following sample from our class’s own game of ECO-BINGO can do a better job of demonstrating the connection. Inspired by the spectrum of interests and the mini-reflections throughout the spring, ECO-BINGO tried to capture the semester’s patterns in twenty minutes in the last class. Each square represented a topic covered in the course. As Professor McNeill read the topics in a random order, each student used their own ECO-BINGO sheet (all of them different) to mark the ones they found personally useful for their ongoing studies. Just as in the regular version, if the student got BINGO, any square marked had to be justified – in this case by proving to the room how it would apply to their project in the future. With the addition of visitors to the class, two PhD candidates and one who had successfully defended, to serve as judges, the pressure was high for succinct, thorough, and compelling reasons that, say, “Animals & Grasslands” would be important to your research. ECO-BINGO served as a fun way to rehash the topics of the semester, but the reflective process struck me as a reminder that, as scholars, we benefit from continually reckoning with our own projects in light of new input. Historians search for patterns in their research, both relying on existing work and uncovering opportunities for study. To be able to do that work requires constant exposure and seeking out ideas, which the classroom setting in the Spring fulfilled so well. I was glad to have registered and now find myself incorporating environmental themes into my own work going forward. Which reminds me that the other known fundamental of BINGO is a little luck. Rebecca Andrews is an incoming first-year PhD student in the Georgetown History department, coming from the department’s MAGIC program the past two years. Her research focuses on themes of family, mobility, and gender in Latin America. Her current interest in chinampa agriculture around Mexico City stems directly from this Environmental History Seminar.

31 Comments

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed