|

Georgetown Environmental History recently sat down with renowned Brazilian environmental historian José Augusto Pádua in Rio de Janeiro to have a conversation about fires and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. We asked him about the relationship between fire and deforestation, the history of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, and who is responsible for the recent surge in deforestation. Check out the video below for his answers. Video Guide What is the relationship between fire and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon? 00:05-02:51 What is the history of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon? 02:52-04:31: Deforestation prior to 1970s 04:32-12:06: Decades of destruction, 1970s-1990s 12:07-15:47: Improvements, 2004-2014 Who is responsible for deforestation in the in the Brazilian Amazon? 15:48-22:01 What was the catalyst for the current crisis (June-October, 2019)? 22:02-30:19. Author Biography

José Augusto Pádua is a professor of environmental history at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s Institute of History, where he is a co-coordinator of the Laboratório de História e Natureza (Environment and History Laboratory). He a specialist in the history of the Brazilian Amazon and has been studying the forest and doing fieldwork there since the 1970s. He is the author of numerous books and chapters about Brazilian environmental history, including “Brazil in the History of the Anthropocene” in Liz-Rejane Issberner and Philippe Léna (eds.) Brazil in the Anthropocene (London: Routledge, 2017), 19-40, “Civil Society and Environmentalism in Brazil: The Twentieth Century’s Great Acceleration” in Lise Sedrez and S. Ravi Rajan (eds.) The Great Convergence: Environmental Histories of the BRICS (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018), 113-134, and “The Dilemma of the ‘Splendid Cradle’: Nature and Territory in the Construction of Brazil” in José Augusto Pádua, John Soluri, and Claudia Leal (eds.) A Living Past: Environmental Histories of Modern Latin America (New York: Berghahn, 2018), 91-114.

0 Comments

Natascha Otoya Environmental history (EH) is still in its infancy in academia, particularly on a global scale, when compared to other fields within the discipline of history. The practitioners of economic history, for example, are preparing for their 19th world gathering in Paris. The most recent World Congress of Environmental History (WCEH) was only the field's third, and it presented environmental historians from around the world with a great opportunity to meet fellow scholars in global EH. The conference also highlighted regional expansions and, more broadly, a global growth of an environmental way of doing history. The 3rd WCEH took place in Florianópolis, Brazil, at the campus of the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) from 22 to 26 July 2019. The event is set to happen every five years, the first being held in 2009 in Copenhagen, Denmark and the second in 2014, in northern Portuguese town of Guimarães. The island city of Florianópolis, in the southern state of Santa Catarina, was an ideal location to host the 3rd World Congress. Not only is the city itself testament to the challenges of human occupation in a delicate natural environment (as islands generally are), but it is home to one of the most active Environmental History Laboratories in the Americas. The Laboratório de Imigração, Migração e Historia Ambiental - LABIMHA - is arguably the oldest of its kind in Brazil, having been created in 1992. Since then, the lab's organizers João Klug and Eunice Nodari have published multiple books and articles, organized several events and supervised many Masters and PhD theses, actively contributing to the regional growth of the field. The 3rd WCEH was truly a global event. Over 300 scholars from 35 countries of every continent came together to discuss their research, debate the challenges of the field, promote books, meet peers and make connections. The vast array of talks, roundtables, panels and experimental sessions represented a challenge for attendees, who had to choose from so many interesting offerings. There were some definite highlights: the opening keynote address by Brigitte Baptiste, the General Director of the Humboldt Research Institute for Biological Resources in Colombia was one of them. Self-described as a queer ecologist, her talk connected biodiversity and sexual diversity in novel and interesting ways while discussing anthropogenic change in what she labeled a transitional world in which humans have substatially transformed nature both in and outside of their bodies. Another highlight was the presence of many prominent scholars in EH. For example, many young scholars and students reported cherishing the unique opportunity to see Donald Worster speak. According to the organizers, his two sessions were the ones that attracted the most attendees. The emerging themes of EH were represented across panels and sessions. New perspectives were brought to traditional topics such as water, energy, animals, landscape, forests and cities. Several comparative panels featured multiple regions of the world, such as China, India, Latin America and Antarctica. Political and cultural approaches helped inform yet other discussions. The attention to the present, the consequences of the Anthropocene, the challenges of teaching EH and the ways in which the environment will shape the future history of humanity were also debated in sessions - and at informal circles after the official program was over. Conferences are a great way to stay connected, see old friends, make new ones, and get to know exciting new research in the field. As such, conferences are an excellent opportunity to strengthen bonds beyond our home institutions and help build a thriving, global community. Scholarly work in history can feel very lonely if confined to libraries and archives. Meeting peers and discussing ways to connect are essential means of overcoming the solitude of reading and writing individually. The days in Florianópolis were particularly fruitful in terms of overcoming this academic isolation and discussing ways of moving from individual production to collaborative work (historians have much to learn from our peers in the natural sciences about the power of collaboration). This was my main takeaway from being at the conference: to see how much greater our contributions can be if we work together as a group. Natascha Otoya is a PhD student of Environmental History at Georgetown University. Her research focus is on the development of the oil industry in Brazil, from early to mid-twentieth century. She is interested in the development of the field of oil geology in the Latin American context and how human interactions with nature were mediated by science and political ideologies.

Matthew Johnson This post is part one of a profile series in which Matthew and Natascha write about notable people in twentieth-century environmental history. What the world knew about the environmental impact of China’s Three Gorges Dam during its early planning stages was largely thanks to the efforts of Chinese journalist Dai Qing. Three Gorges Dam is a giant dam on the Yangtze (Yangzi) River that the Chinese government erected during the 1990s and 2000s. It is the world’s largest hydroelectric dam in terms of installed capacity—it can produce an impressive 22,500 megawatts—and is one of the world’s most controversial dams because it had a huge social and environmental footprint. The Three Gorges Dam was an old dream among modern Chinese engineers. The Republic of China’s first president Sun Yat-sen first envisioned building a dam at the Three Gorges in 1919, but political and economic challenges prevented the project from getting off the ground. It was not until the mid-1980s that the Chinese government resurrected the plans with the resources to see it completed. In 1988, Dai read about the project in her local newspaper. The following February she published Yangtze! Yangtze!, a collection of essays from forty scientists, economists, and journalists who opposed the dam. The essays warned that the Three Gorges Dam would have grave social and environmental consequences, such as the displacement of over one million people, and advised the Chinese government to reconsider its decision to build the dam. Dai’s collection was the first time that the public had heard about the negative impacts of Three Gorges, as engineering and impact studies had been carried out secretly. The revelations ignited one of the first environmental debates in modern Chinese history. Yangtze! Yangtze! earned Dai the dangerous label of dissident, and after she renounced her membership to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) following the Tiananmen Square protests in June 1989, the government arrested her. Dai spent ten months in the Qincheng prison north of Beijing, enduring six of those months in solitary confinement. In October, eight months after publication and four months after Dai’s arrest, the Chinese government banned the collection and destroyed all the copies it could find. Dai was no stranger to rebellion and its consequences. She was born in Chongqing in 1941 to parents that had close connections with founding members of the CCP. When the Japanese occupied China during World War II, Japanese soldiers captured and tortured her mother and executed her father. In the 1960s, she studied military and missile engineering in school and after graduation, she got a job working on guidance systems for intercontinental missiles in a secret government lab. However, Dai became disillusioned with the CCP during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and protested by marrying and getting pregnant before the approved age. As punishment, the government sent Dai and her husband to work on a farm. She became further disenchanted with the CCP when she found out that they had tortured her mother and stepfather, the latter of whom was driven to insanity and died shortly thereafter. In the 1970s, Dai returned to Beijing and began working as a spy for the Ministry of Public Security. During one of her missions the Ministry sent her to France disguised as a journalist. She played the part well and found that she actually liked writing stories. In 1982, she lost her job as a spy because colleagues exposed her identity to foreign intelligence agencies, but she had become so enamored with journalism that she decided to take up writing full time. Yangtze! Yangtze! and the protests it inspired had an impact. In 1993, the US Bureau of Reclamation withdrew financial and technical support for the dam and the World Bank decided against funding the project. However, protests could not halt construction, and the government went ahead with the project despite the loss of international support. Construction began in 1994 and its reservoir filled in 2006. Its thirty-second and final turbine was finished in 2012. In 1993, Dai won the Goldman Environmental Foundation’s prestigious annual prize—which is also known as the Green Nobel Prize—for her activism against the Three Gorges Dam. Ironically, Dai does not identify as an environmentalist. She considers herself an investigative journalist fighting for democracy and human rights. She is a political moderate and tries to use that to her advantage as an interloper between the government and the democratic movement. Despite not being a self-identified environmentalist, Dai played a vital role as an environmental defender during one of the twentieth-century’s grandest and most controversial environmental re-engineering projects. Her fearlessness and dedication to democracy brought international attention to the environmental consequences one of the world’s largest dams. Though she could not stop the dam, her efforts raised awareness about the negative impacts of mega dams, which helped to reduce their appeal among international lending agencies. For more information on Dai Qing and her fight against the Three Gorges Dam see: Dai’s page on the Goldman Foundation’s Environmental Prize website and Allison Griner’s March 2016 article in Al Jazeera. For more information on the Three Gorges Dam, see the United States Geological Survey’s summary webpage. Digital copies of Yangtze! Yangtze! and Dai’s 1998 follow up The River Dragon Has Come! can be found on Probe International’s website. An annex in the digital copy of Yangtze! Yangtze! includes a historical timeline of the project and the preface to The River Dragon Has Come! has a detailed history of both Dai Qing and the Three Gorges Dam. Matthew P. Johnson is a PhD candidate at Georgetown University who studies modern Latin American and Caribbean environmental history. His dissertation examines the social and environmental consequences of hydroelectric dams built by Brazil’s military government in the 1970s and 1980s.

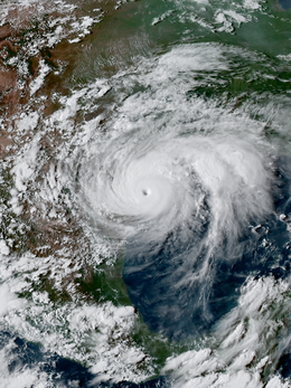

Clark Alejandrino A year ago, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria made headlines by wreaking havoc in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan took more than 6,000 lives in the Philippines. Thanks to modern meteorology and the ease of information dissemination on the internet, people knew these storms were coming and how strong they were and yet we still managed to end up with varying degrees of humanitarian disasters. One can only imagine how these storms must have taken people by surprise in the past. Well, not exactly. Along the southern Chinese coast, for centuries people looked to nature for signs and omens of a typhoon. Locals thought birds had a way of sensing storms and displayed this understanding through their behavior. Suddenly seeing seabirds fly toward the mountains in flocks meant a storm was coming. When birds that normally build nests in high places start building them low also meant a typhoon was approaching. At the start of the year, people would look at the leaves of the plant Eragrostis ferruginea and count the number of lines on it for each line meant one storm was coming that year. In Taiwan, this plant is still known as the typhoon plant 颱風草 (taifengcao). One omen that has a history as old as the Tang dynasty (618-907) is the so-called Typhoon Mother 颶母(jumu). The Typhoon Mother was a combination of red clouds and split rainbows in the ocean sky that people believed surely heralded the coming of a typhoon. Twenty-first century Chinese government documents continue to list it as one of the signs to look out for heading into typhoon season. To us today, reading leaves, birdwatching, and staring at clouds and rainbows sound like things to do on a nice sunny day. But along China’s southern coast, people used to do these things to prepare for a stormy day. Perhaps these methods are less precise than going to WeatherChannel.com but at least they got you out of the house and emphasized, in a more observant way, our interconnectedness with the environment. Clark Alejandrino is a Georgetown PhD Candidate in East Asian Environmental History writing his dissertation on typhoons in southern China from the fifth to the twentieth century.

Rebecca Andrews “B seven. G twenty-four. O eighteen.” As the announcer neatly ticks off the options that could let you take home that BINGO prize, the apparently random assortment of numbers in front of you begin to take on shape. Patterns emerge and your excitement increases with every square that connects. But, as any seasoned BINGO player will tell you, listening for the next one is as important as marking down the ones previously read. If you fall behind because you over-celebrated getting the second to last block, you may miss the announcement of your winning square. Finding what the pattern looks like, seeing the gaps of what you need next, and paying attention are, in my view, the fundamentals of BINGO. As it happens, these could also be considered the fundamentals of my experience this past semester in Professor McNeill’s Environmental History Seminar. Professor McNeill began the seminar asking all five students to nominate themes for discussion throughout the semester. The topics suggested ranged widely, from “Big History” and “Energy” to “Urban Metabolism,” showing the varied interests and priorities of the room. As a newcomer to environmental history, the full blackboard and resulting skeleton syllabus was my first exposure to a summary of which historical themes might mesh well with environmental thinking. As it turned out, that appeared to be pretty much anything – a random assortment of topics to an inexperienced eye. As the semester proceeded, patterns emerged. Historical and environmental questions blended together and grew from class to class. What does it mean to write accessibly? What about scientifically? What do we, as both historians and readers, gain from including and exploring the materiality of our subject matter? Some were more detailed (what is copper, bison, or soil, anyway?) and some were much bigger (should every history start with the Big Bang?). With each new idea, every class encouraged a reassessment of your own work with a fresh environmental perspective or a new method. The weekly exercise of identifying “grist for your mill” encouraged us to layer concepts on individual projects, paying attention to what’s out there and assessing how it had been applied. Reading, listening, thinking, and debating the way through each book created more informed views of what gaps existed. If in reading the last three paragraphs you did not immediately think to yourself, “Now this looks a lot like the fundamentals of BINGO,” don’t worry. Maybe the following sample from our class’s own game of ECO-BINGO can do a better job of demonstrating the connection. Inspired by the spectrum of interests and the mini-reflections throughout the spring, ECO-BINGO tried to capture the semester’s patterns in twenty minutes in the last class. Each square represented a topic covered in the course. As Professor McNeill read the topics in a random order, each student used their own ECO-BINGO sheet (all of them different) to mark the ones they found personally useful for their ongoing studies. Just as in the regular version, if the student got BINGO, any square marked had to be justified – in this case by proving to the room how it would apply to their project in the future. With the addition of visitors to the class, two PhD candidates and one who had successfully defended, to serve as judges, the pressure was high for succinct, thorough, and compelling reasons that, say, “Animals & Grasslands” would be important to your research. ECO-BINGO served as a fun way to rehash the topics of the semester, but the reflective process struck me as a reminder that, as scholars, we benefit from continually reckoning with our own projects in light of new input. Historians search for patterns in their research, both relying on existing work and uncovering opportunities for study. To be able to do that work requires constant exposure and seeking out ideas, which the classroom setting in the Spring fulfilled so well. I was glad to have registered and now find myself incorporating environmental themes into my own work going forward. Which reminds me that the other known fundamental of BINGO is a little luck. Rebecca Andrews is an incoming first-year PhD student in the Georgetown History department, coming from the department’s MAGIC program the past two years. Her research focuses on themes of family, mobility, and gender in Latin America. Her current interest in chinampa agriculture around Mexico City stems directly from this Environmental History Seminar.

|

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed