|

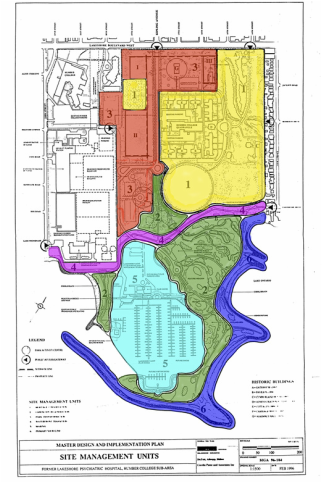

Meredith Denning On January 29, Prof. Adam Rome is coming to Georgetown. Ahead of his visit, I’ve been re-reading The Bulldozer in the Countryside (2001) and thinking about the landscape that shaped my interest in environmental change. Rome’s work addresses the American environmental movement and explores how post-World War II suburban landscapes shaped perceptions of environmental change just as powerfully as traditionally ‘natural’ landscapes like the National Parks. New Toronto, where I grew up, is not exactly a Baby Boom suburb. Laid out as a self-contained manufacturing town at the turn of the twentieth century, it has an electric streetcar running down the main street twenty-four hours a day, three bus lines and two commuter train stations. A car is hardly necessary and the layout is classic urban Ontario, with tidily numbered streets and high-density amenities like a greengrocer, a fish-and-chip shop, cafes, and a third-generation cobbler. However, one of Rome’s points in Bulldozer resonates for me, and that is the powerful impact that witnessing the transformation of a landscape can have upon a person. I also find myself thinking about how useless it is to try to distinguish between ‘natural’ and ‘human’ landscapes. If you take the bus to the foot of Kipling Avenue today, you’ll find yourself in a very interesting space. An old mental hospital and its extensive grounds have been converted into a variety of spaces for the human community: an ice-skating ‘trail,’ an assembly hall and gallery, part of a community college campus, a new high school and spaces for ‘nature’: turtle nesting habitats, fish nurseries, and meadows of native grasses. This assemblage is the result of several decades of urban design and it’s a fascinating layer cake of meaning for the environmental historian. The map (below, right) shows the space, coloured according to the six site management units that were adopted as part of an Etobicoke City Council resolution in 1997:  1. Heritage Conservation (yellow) 2. Landscape Regeneration (green) 3. Park Transformation (orange) 4. Waterfront Transition (purple) 5. Boating Basin (lt. blue) 6. Primary Shoreline (dk. blue) When my family moved to New Toronto in 1990, the ‘hospital grounds’ were just starting to be turned into this brightly delineated Colonel Samuel Smith Park. I spent much of my free time exploring that space and I knew it like the back of my hand. I knew every pothole in the old road that led from the main street down towards the lake, twisting past disused asylum buildings with broken windows until it reached the one residential building still in use. I knew every footpath that bird-watchers, dog-walkers and pot-smoking teenagers had carved through the underbrush of the forest tract. For most of my childhood, using the waterfront was illegal because it was literally under construction. The shoreline of the new park is made of landfill, and soil was still being moved in by the truckload. Nobody that I ever saw paid any attention to the ‘Do Not Enter’ sign, since anywhere a truck can drive, a bike or a birdwatcher can follow. The wire fence at the base of the peninsula was permanently ground into the dirt by passing feet. There I learned that the people who use a space daily make their own determinations. Huge slabs of concrete, their rusted steel reinforcements sticking out, were dumped to form a coast with many small inlets. Nobody tries to hide these plain signs of created ‘extra’ land, even now. Perhaps their presence indicates our growing comfort with created/natural landscapes, or perhaps the city’s budget was too small. In any case, the inlets are designed to shelter birds and turtles, but they also make good beaches for bonfires, excellent perches for a quiet talk, and multilevel jungle gyms for kids to explore. The occasional broken beer bottle between the ‘rocks’ never makes much of an impression in the face of the grand stillness of a Great Lake. Eventually, the government opened up the new park. I knew the trees there well, and I watched them change as the last phase of landscaping unfolded.There were trees that were best for sitting, some were made for climbing, some served only for hide-and-seek. My dad still scratches his head sometimes, looking for his third-best hammer. I’ve never told him that I lost it in a big willow tree there. (My friend Denise and I decided to improve somebody else’s treehouse, and I blithely assumed that tools in a bike basket on a branch would be left untouched). The old orchard, mentioned in some local histories, is all gone now. The treehouse willow gave way to a parking lot for the new skating trail. I hear this place called many things. The oldest residents still call it ‘the looney bin’ or ‘the hospital grounds.’ In my head, it’s still just ’the big park,’ a schoolyard name that made sense if your mental map was only a few kilometres wide. Sometimes one hears, ’Sam Smith,’ a version of the formal name. Only the newest arrivals call it by names that suggest its current functions: ‘the Humber campus,’ ‘the figure eight’ (meaning the skating trail), or ‘the Assembly Hall.’ Clearly, the old hospital grounds are a largely human construction and their current iteration, for all its emphasis on resorting native species and providing habitat, is as consciously confected as the asylum's gardens ever were. Watching the transformation from neglected lawns and orchard to an ’multi-use urban wilderness’ during my lifetime convinced me that habitat restoration is possible. The number and variety of birds, fish, mammals, and other creatures has increased dramatically since I first biked around the peninsula construction site. At the same time, marshalling the money and political will to change this large space brought many new tenants and much more activity. The dark, silent asylum buildings are busy classrooms and the marsh birds build safe nests in the long grasses by the shore. If you’re curious to learn more about this place, here are some links: Profile by the Cultural Landscape Foundation, an American NGO: https://tclf.org/landscapes/colonel-samuel-smith-park Very quick local history: http://torontoplaques.com/Pages/Colonel_Samuel_Smith_Park.html Citizen’s waterfront association: http://www.ccfew.org/html/sam_smith_park.html A local birder’s website, long to load but with wonderful wildlife photography: https://burlingtonontariobirder.wordpress.com/tag/colonel-samuel-smith-park/

2 Comments

4/3/2023 04:33:17 pm

Extremely pleasant article, I delighted in perusing your post, exceptionally decent share, I need to twit this to my devotees. Much obliged!.

Reply

4/4/2023 01:12:08 pm

The New Toronto, where I grew up, is not exactly a Baby Boom suburb. Laid out as a self contained manufacturing town at the turn of the twentieth century, Thank you for making this such an awesome post!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

EH@G BlogArticles written by students and faculty in environmental history at Georgetown University. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed